Karachi LaJamia (KLJ), literally Karachi Un-University, was conceived of as an experiment in 2015 — Can we teach and learn outside the confines of traditional schools? What becomes possible here? “We wanted to create a space for community outside the institution, for connection in an increasingly bordered and fragmented city,” its founders, artists Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani tell us about how the project was born. Since its founding, KLJ has approached its work with flexibility and ingenuity — creating courses such as Hamare Siyal Rishte exploring disappearing rivers and climate crises, syllabi such as Stateless Study composed of six exercises to encourage new ways of understanding land, memory and embodiment, exhibited at the Jameel Arts Centre in 2022, and organising research groups such as one convened in Gadap Town, Karachi to document the displacement of its indigenous communities in light of Pakistan’s rapid urban development.

Karachi LaJamia grows in unexpected and mycelial ways, collaborating with other organisations, artists and activists, working “slowly and at small scale… with caution and sensitivity.” We speak to Rajani and Malkani about how they navigate the spaces they conjure.

Let us begin with the notion of collaboration. In many ways your practice is a practice of collaboration itself. Could you speak to how participants, collaborators and collaborative moments have shaped Karachi LaJamia (KLJ)?

Collaboration has been the heart of our practice—it was our mutual need to work collectively and build community in Karachi that first brought us together. We wanted to refuse working in isolation and the myths of the individual genius. We were both teaching at universities and art schools at the time, and wanted to challenge the idea of learning and studying as individual, solitary acts. We also saw how securitised and disconnected schooling had become from the communities, land and ecologies of the city. And so KLJ started as our way of moving outside the walls of institutions, to situate art practice and pedagogy in the larger urban context, in public space.

Over the years, we have closely collaborated with local community and activist organisations fighting against development and militarisation, to facilitate a series of public courses in the city. We have benefited immensely from our conversations and collaborations with the Indigenous Rights Alliance, the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum, the Syed Hashmi Reference Library among others. Our work also draws from the wisdom and research of academics such as the late Gul Hassan Kalmatti, Perween Rehman, Nausheen Anwar and Noman Ahmed. Each of these collaborations and readings has profoundly transformed us, our practice and our relationship to the city.

We are constantly learning from activists, indigenous scholars and community organisers—from their immense wealth of knowledge, their generosity of spirit and their continued determination to speak truth to power. It is these friendships and collaborations that have taught us that knowledge is always meant to be produced and shared in and with community, and we seek to extend the same spirit of care and hospitality through our work.

In your work as KLJ as well as in your individual practices, ‘work’ is not a stable object, but something changeable, moving and belonging to particular times and moments. Can you describe your move away from object-based art-making?

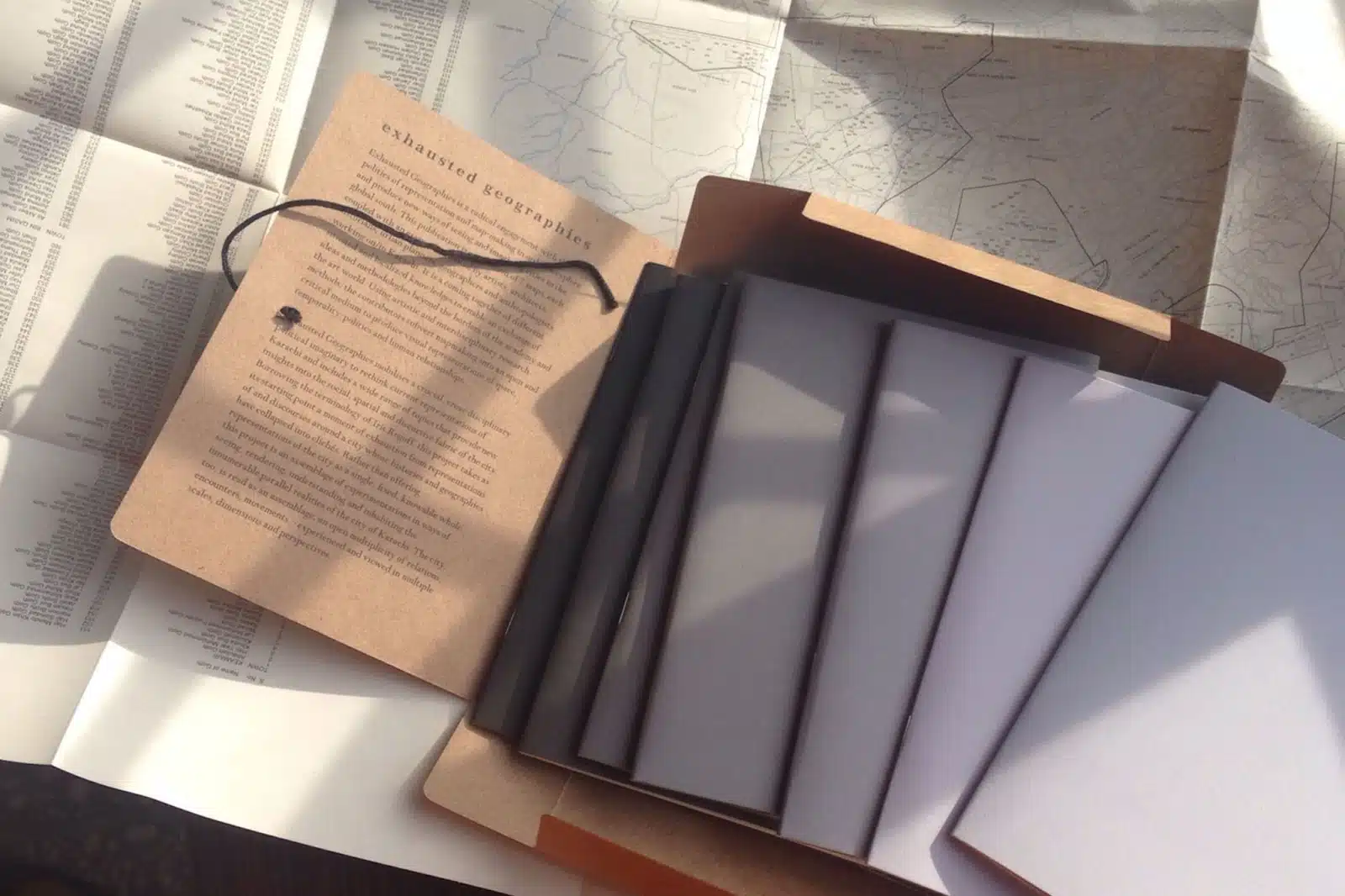

When we started KLJ, we wanted to step outside the art school and the art gallery, to connect our practices more deeply with the city. Part of this move came from a political desire to engage and work outside the confines and dictates of the art market. But it also came from a need to find and create our own spaces and communities because the kind of work we were making did not fit the object-centered economies of art. Earlier, we had responded to this dilemma by turning to the medium of print and publications. It enabled us to share, process and circulate our work with greater freedom and agency, to build and expand our audiences. Exhausted Geographies was our first publication and we are still amazed by the afterlife of this project, how many people it managed to reach.

We also draw on and learn from the long and rich traditions and histories of print publishing ephemera within activist and community spaces. The print medium has long been used by activists to nurture counter publics, environmental movements, political imaginaries and radical aesthetic and cultural practices. These publications often had discreet, intimate circulations that mobilised communities. They were cheap, ephemeral and relatively easy to print. They could be carried in one’s pocket, stored and hidden, discarded if needed. It was their fluid, discreet, almost anti-exhibitionary potential that made them so useful. We embrace these qualities of the print medium. We often produce pamphlets, study guides and photocopy syllabi to share ongoing research in fragments. These informal forms mean that ongoing research can be shared and circulated without having to be packaged as a ‘finished’, overdetermined product.

However, KLJ was never meant as a withdrawal from or forsaking of the gallery or the university. The work and research that we do in and about the city, we are really invested in bringing those knowledges and pedagogies back into institutional spaces, to work towards transforming them. The practices of pedagogy and collectivity that we have learned through our collaborations, we want to bring those into the exhibition space. To ask the viewer to engage and relate differently. As KLJ, we have produced a great deal of research and writing studying the colonial history of our art and educational institutions and their ongoing relationships with the military development nexus. So we are not under any naive illusions about the radical potential of these spaces. Yet, in the context of widespread institutional collapse and the extreme scarcity of cultural spaces and funding in Pakistan, we want to take advantage of the resources and reach that existing spaces could offer.

“In a sense, this is a faith-based practice. Faith in the relationships and communities we come from and the relationships and communities we reach towards.”

In recent exhibitions, we have been trying to create gathering spaces that are hospitable to people other than the usual art audiences. These spaces embody and reflect the community spaces and environments in which we work, and where our practices are devised, shared and circulated, which include community libraries, roadside dhabas, boats and autos. We want to facilitate an immersive experience in which audiences encounter our research and pedagogical materials in a space that reflects visually and aurally the spirit, the intensity and the intimacy of the contexts we work in and the contexts we create. A space for connection and collective witnessing.

Where do you draw inspiration from? Are there other artist initiatives or creative models of community work that have significantly shaped your work?

There are some very exciting collective artist-run initiatives happening in the South Asia region we are inspired by. Especially in Nepal, the Nepal Picture Library and Kala Kulo are doing very exciting work. In Bangladesh, there are some incredible artists doing great pedagogical work at Pathshala. We have often been in conversation with The Packet in Colombo over the years. We love the work of Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam in Dharamshala. Other Cinemas in London is another great project we are inspired by. Our friends at Amrit Pyala are also doing some incredible archiving work in Pakistan.

What kind of archives, knowledge or reference points are you creating with Karachi LaJamia?

As much as Karachi LaJamia’s courses are about bearing witness to the devastation of capital, militarism and extractivism in this particular moment—we are also devoted to acknowledging and studying the long and rich history of resistance this land has nurtured. The widespread losses of landscapes, ecologies and species we face in this moment of crisis also entail a concomitant loss of devalued indigenous culture, language and knowledges. Our practice is motivated not only by a desire to intervene upon discourse in this particular historical moment, but also by a desire to archive, preserve and expand upon the cultural, linguistic and pedagogical practices from our region that are at greatest risk, and that we hope to animate and keep alive for generations to come. This often happens in ways that we cannot predict or control. In a sense, this is a faith-based practice. Faith in the relationships and communities we come from and the relationships and communities we reach towards.

Karachi LaJamia (founded 2015) is an experimental pedagogical project co-founded by artists Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani. The collective is the recipent of the 2025 Asia Arts Future Award (South Asia) presented by Asia Society India.