Be it Maharashtra’s Warli wall paintings, Andhra Pradesh’s Kalamkari textiles or West Bengal’s Kalighat bazaar art, each corner of India has its own folk art legacy, going back centuries and millennia. While each of these art-forms are based on distinct styles, techniques and themes, they share in common a celebration of community and narrative—and together tell the layered story of India through the ages. Here, we meet ten contemporary artists who carry forward their folk traditions into the 21st century, paying homage to history while unlocking the expressive potential of each style to tell new stories of today and tomorrow.

1. Ajit Kumar Das, Kalamkari

Ajit Kumar Das. Jeevan Taru 2, Year Unknown. Handpainted with natural dyes on cotton textile. Courtesy of Gallery Art Motif.

Ajit Kumar Das. Jeevan Taru 2, Year Unknown. Handpainted with natural dyes on cotton textile. Courtesy of Gallery Art Motif.

“An alchemist of natural dyes,” Ajit Kumar Das has been practising and developing the centuries old Kalamkari technique of dyeing and printing for more than fifty years. Hailing from the North-East Indian state of Tripura, Das began his artistic career as a printer at the Weavers Service Center in Ahmedabad where he trained with renowned Indian modernists like C. Chandramouli and K.G. Subramanyam, and was influenced by curators like Martand Singh, who on seeing Das at work, said it was like watching a dancer move. To create his works, Das uses the kalam or bamboo reed, block printing and dyeing to create flora, fauna and abstract forms on textile. Drawing from traditional dyes, techniques and aesthetic sensibilities, Das has developed a visual language that evokes a purity and elegance of colour and form.

2. Kalam Patua, Kalighat

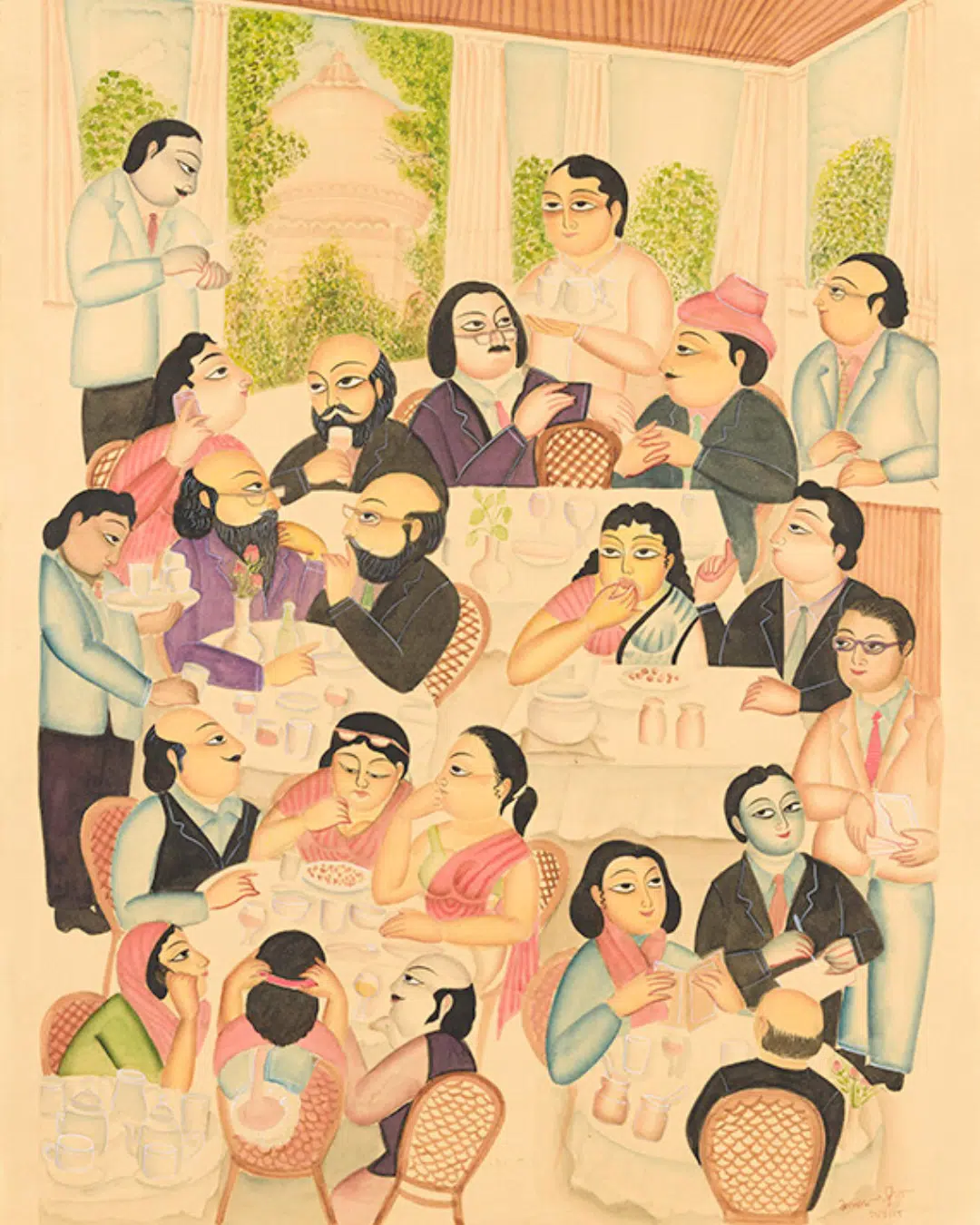

Kalam Patua. Restaurant, 2015. Courtesy of Inherited Arts Forum.

Kalam Patua. Restaurant, 2015. Courtesy of Inherited Arts Forum.

At 60, Kalam Patua is one of the most celebrated Kalighat artists working today. The artist is credited for breathing new life into the once hugely popular ‘bazaar’ art form from Kolkata, known for its bold lines, bright colours and sharp satire and which has been in decline since the advent of photography.

Hailing from the Rampurhat district of West Bengal into a family of pattachitra scroll-makers––practitioners of the ancient narrative painting tradition from East India from which Kalighat painting eventually evolved in colonial Calcutta––Patua began painting under his uncle and mentor, Baidyanath Patua.

Much like the Kalighat painters of 19th century Calcutta, Kalam Patua’s artworks melds Hindu religious mythology and the images of the modern urban elite, critiquing both with innocent humour. The artist’s own life bleeds into his work too, such as in his ‘Post office’ series, directly inspired by his day-profession as the postmaster of his local post-office.

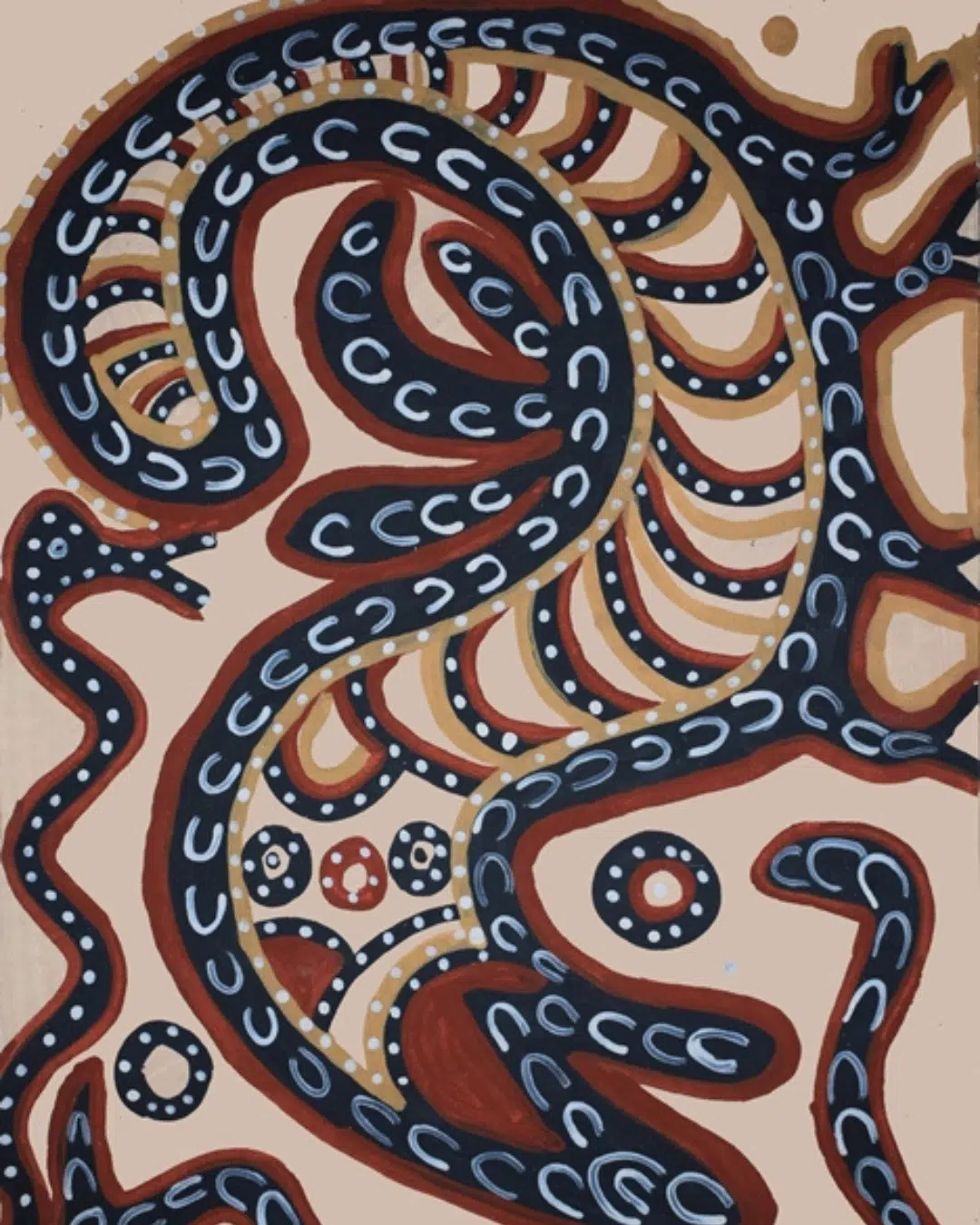

3. Bhuri Bai, Bhil

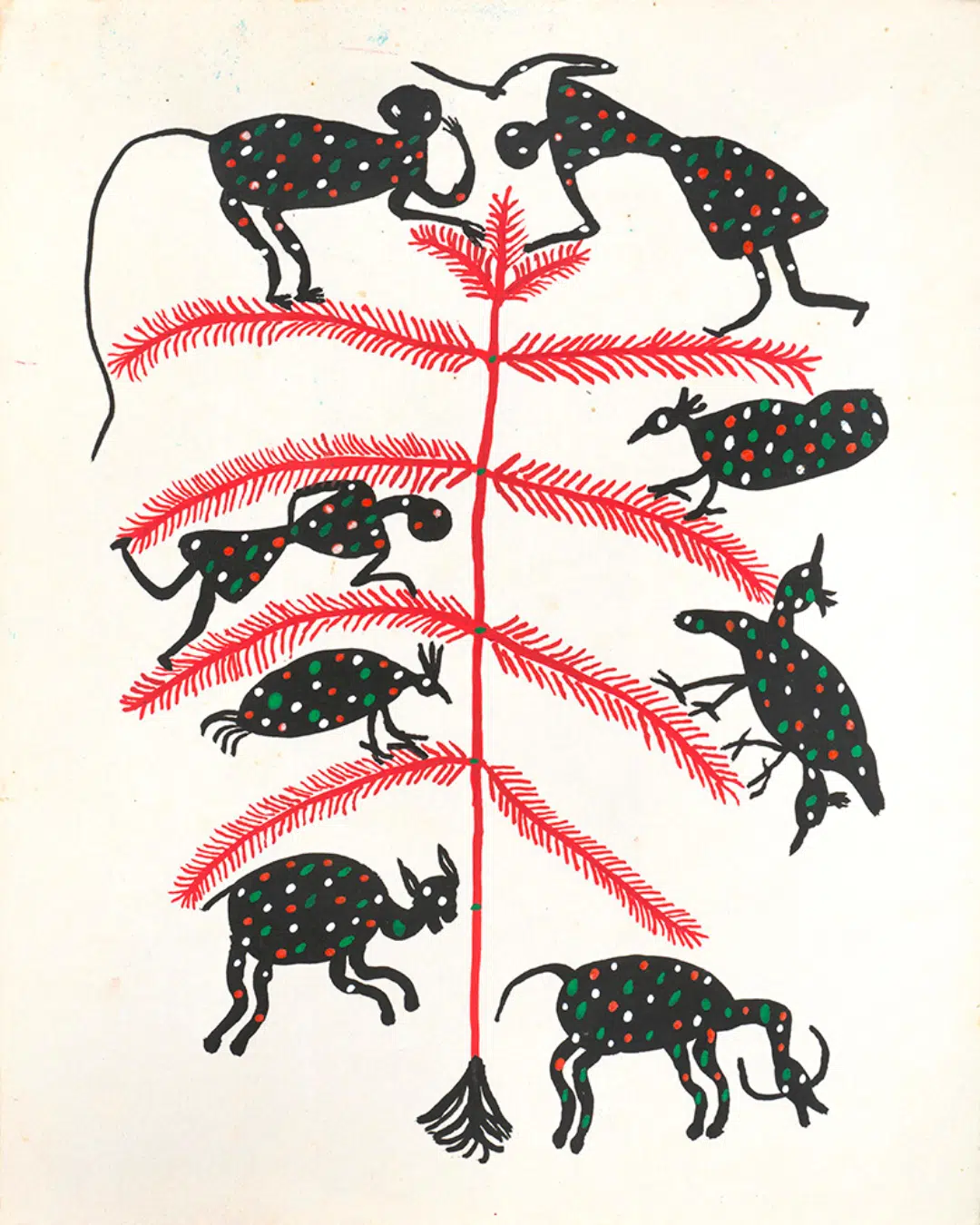

Bhuri Bai. Untitled, 1980. Poster colour on paper. Courtesy of MAP India.

Bhuri Bai. Untitled, 1980. Poster colour on paper. Courtesy of MAP India.

Born in 1969 into a family from the Bhil tribe in Pitol, Madhya Pradesh, Bhuri Bai was the first woman from her community to take up painting, against all convention. While working as a construction worker, she would paint at home and eventually covered the walls of her house with colourful forms resembling plants, humans and animals.

Encouraged by artist and writer J. Swaminathan to live and work out of Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal, the artist gained recognition for her unique vision and crossed over to painting with acrylics on canvas, the first Bhil artist to do so. In keeping with the traditional techniques of Bhil art, Bhuri Bai uses bright colour and dotted patterns to enliven large and imaginative scenes of human and animal figures.

In paintings such as Story of the Jungle, in which a whale transforms into an aeroplane, and Antelopes with Birds, a simple scene of an antelope rendered in almost psychedelic patterning, we see the artist’s ability to remain true to the techniques of Bhil art while using them to express a new aesthetic. A recipient of the fourth highest Indian civilian award, the Padma Shri Award in 2021, Bhuri Bai continues to teach the traditions and techniques of Bhil art to young girls in her village.

4. Bhajju Shyam, Gond

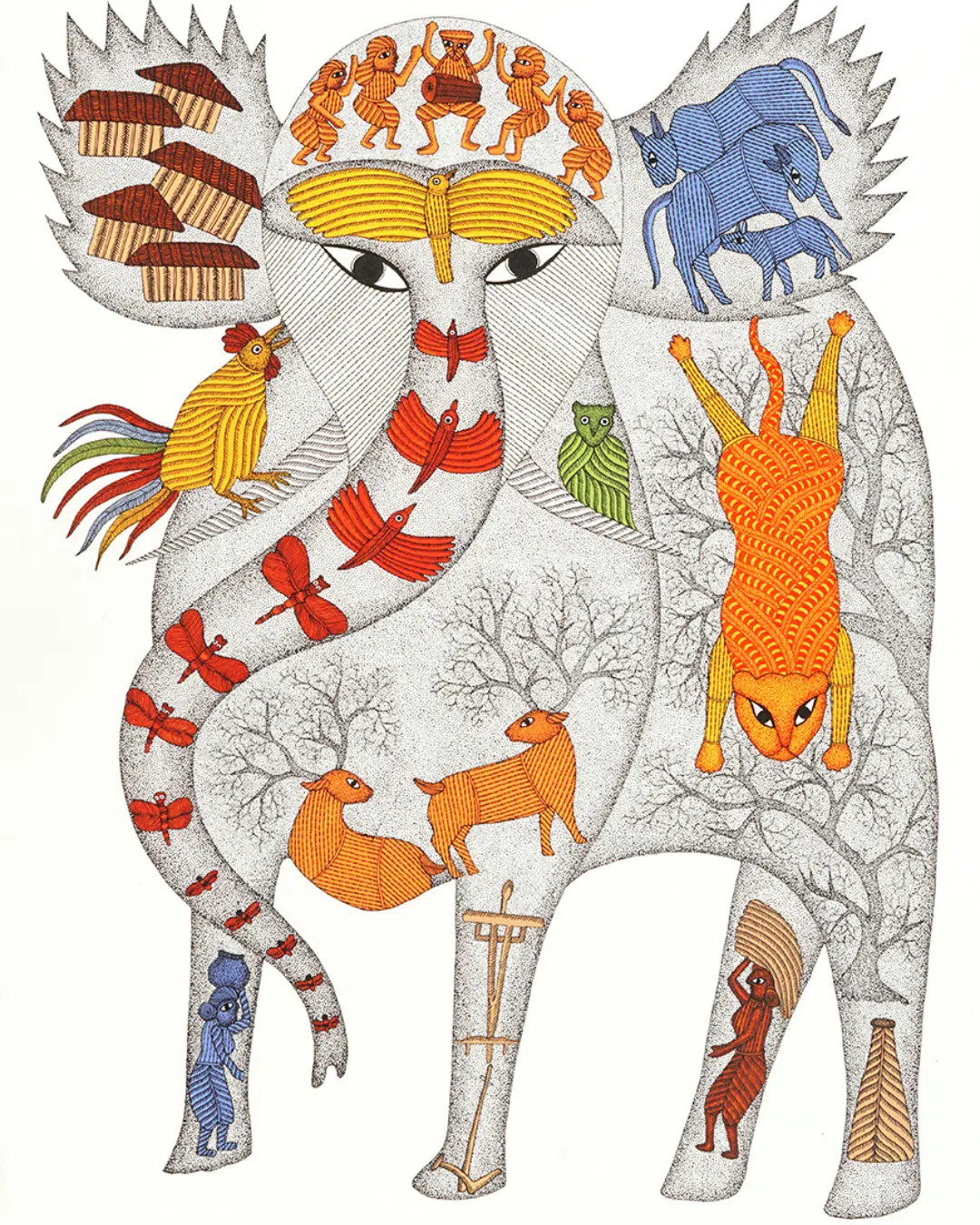

Bhajju Shyam. Riwaaz, 2019. Courtesy of Aakriti Art Gallery.

Born in 1971 in the Gond-Pardhaan village of Patangarh, Madhya Pradesh, Bhajju Shyam is a prominent painter in the Gond tradition who began his journey in art observing and assisting his uncle, Jangarh Singh Shyam, the now-late artist who almost single-handedly brought Gond art to the world stage. Much like in his uncle’s works, many of which now hang in his house in Bhopal, Bhajju Shyam’s works on canvas and paper use motifs from the natural world, with abstracted lines and colours, to explore philosophical and mythical themes such as the creation of the world and the meaning of art. In these large vibrant paintings, as well as in his illustrations or recent paper cut-outs, Shyam is equally inspired by his rural roots and travels around the world, employing traditional Gond techniques to depict modern life and personal experiences. With many international exhibitions and publications, Shyam was awarded the fourth highest Indian civilian award, the Padma Shri in 2018.

5. K.M. Singh, Pichvai

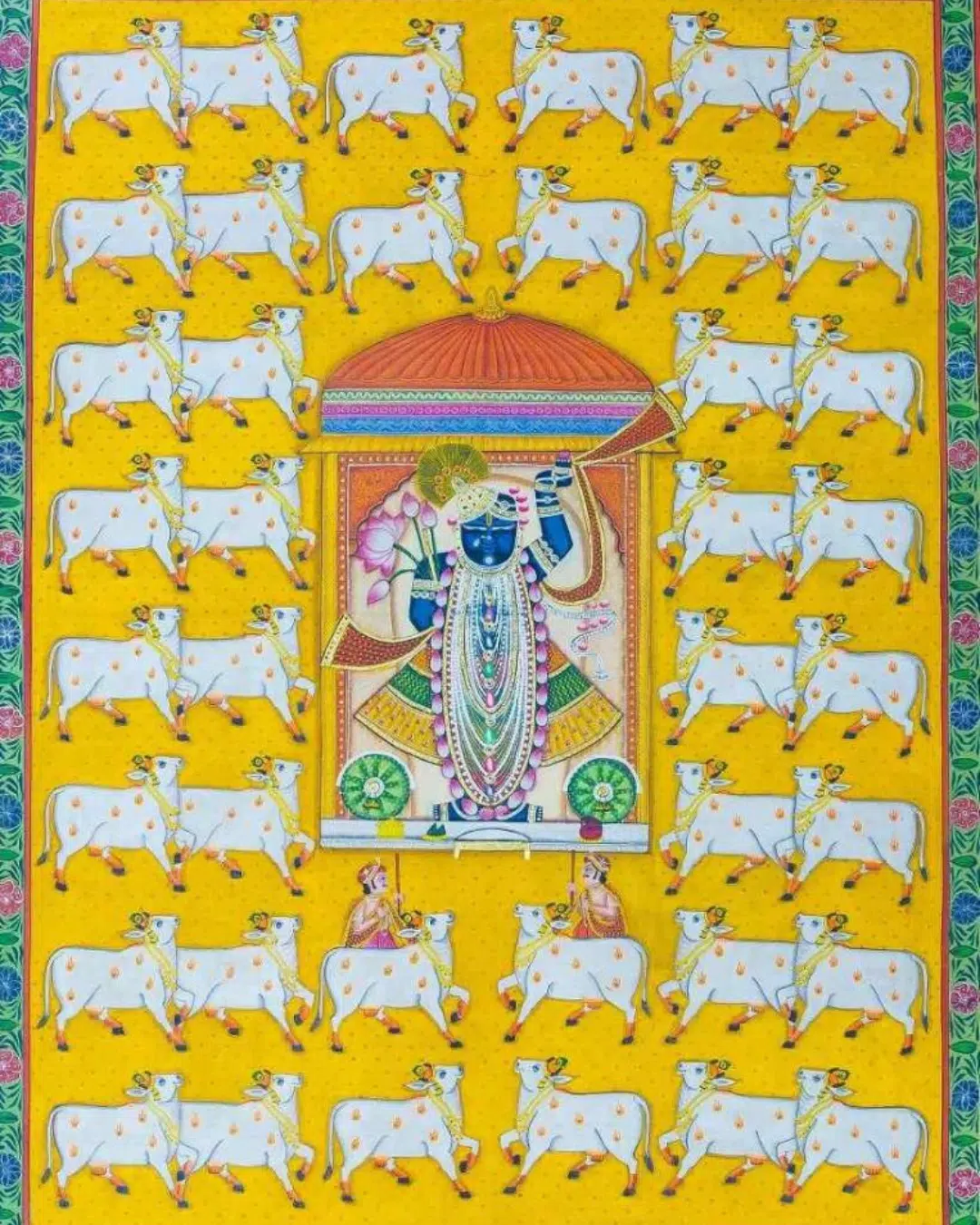

K.M. Singh. Untitled, Year Unknown. Stone Colours on Cotton Fabric. Courtesy of Gallery Ragini.

K.M. Singh. Untitled, Year Unknown. Stone Colours on Cotton Fabric. Courtesy of Gallery Ragini.

Born in 1971, K.M. Singh belongs to a long line of Pichvai artists from Nathdwara in Rajasthan, making devotional and intricate textile paintings that pay homage to lord Krishna as a young child. In many of Singh’s works, the young Krishna, also known as Srinathji, takes centre stage, adorned with jewels, flowers and garlands, and surrounded by a rich cast of religious figures and icons. Working under the patronage of the ancient Shrinathji temple in his hometown, Singh draws his subjects and motifs from tradition, but with a rare mastery of colour and composition that can transcend and transport viewers. Today, many Pichvai artists are also experimenting with newer styles, including hyper-realistic painting inspired by artists such as the modernist Raja Ravi Varma.

6. Putli Devi, Malo Devi and Parvati Devi, Hazaribagh

Parvati Devi. Title unknown, Year unknown. Acrylic on paper. Courtesy of Arts of the Earth India.

Parvati Devi. Title unknown, Year unknown. Acrylic on paper. Courtesy of Arts of the Earth India.

Putli Devi, Malo Devi and Parvati Devi are painters and muralists celebrated for championing the traditional wall art of Hazaribagh district in Jharkhand. Murals with exquisite representations of flora and fauna, traditional Hazaribagh art has two distinct forms—Khovar murals, created during weddings using a ‘reverse-slip’ technique in which layers of black and white earth pigments are applied, let dry and scraped out using combs; and Sohrai murals created during the winter harvest using red ochres, yellows and blacks to depict symbols of wealth like the lord of animals or Pashupati. The three artists each have their specialisms, with Malo Devi being known for Khovar and Putli Devi and Paravti Devi for Sohrai. The artists use their imagination as much as traditional images in their work, often painting from memory of childhood experiences. The women artists represent a swindling community of Hazaribagh artists, as Putli Devi explains, “what is special about the art form is that it is only made by women and passed on by women, and a handful of them at that.”

7. Chanchal Chakraborty, Metal art

Chanchal Chakraborty. Tree of Life. Courtesy of Delhi Crafts Council.

Chanchal Chakraborty. Tree of Life. Courtesy of Delhi Crafts Council.

A maestro of brass sculpture, Chanchal Chakraborty was trained in Chemistry in Shantiniketan, West Bengal, and began his career as a bronze sculptor after moving to New Delhi in the 1990s. Chakraborty uses sand-casting to create his works that are typically treated with chemical washes to create a patina finish. Best known for his works that use natural and spiritually significant forms like that of the lotus flower or Mahabodhi tree, Chakraborty received the National Award in 2012 for his mastery of bronze sculpture.

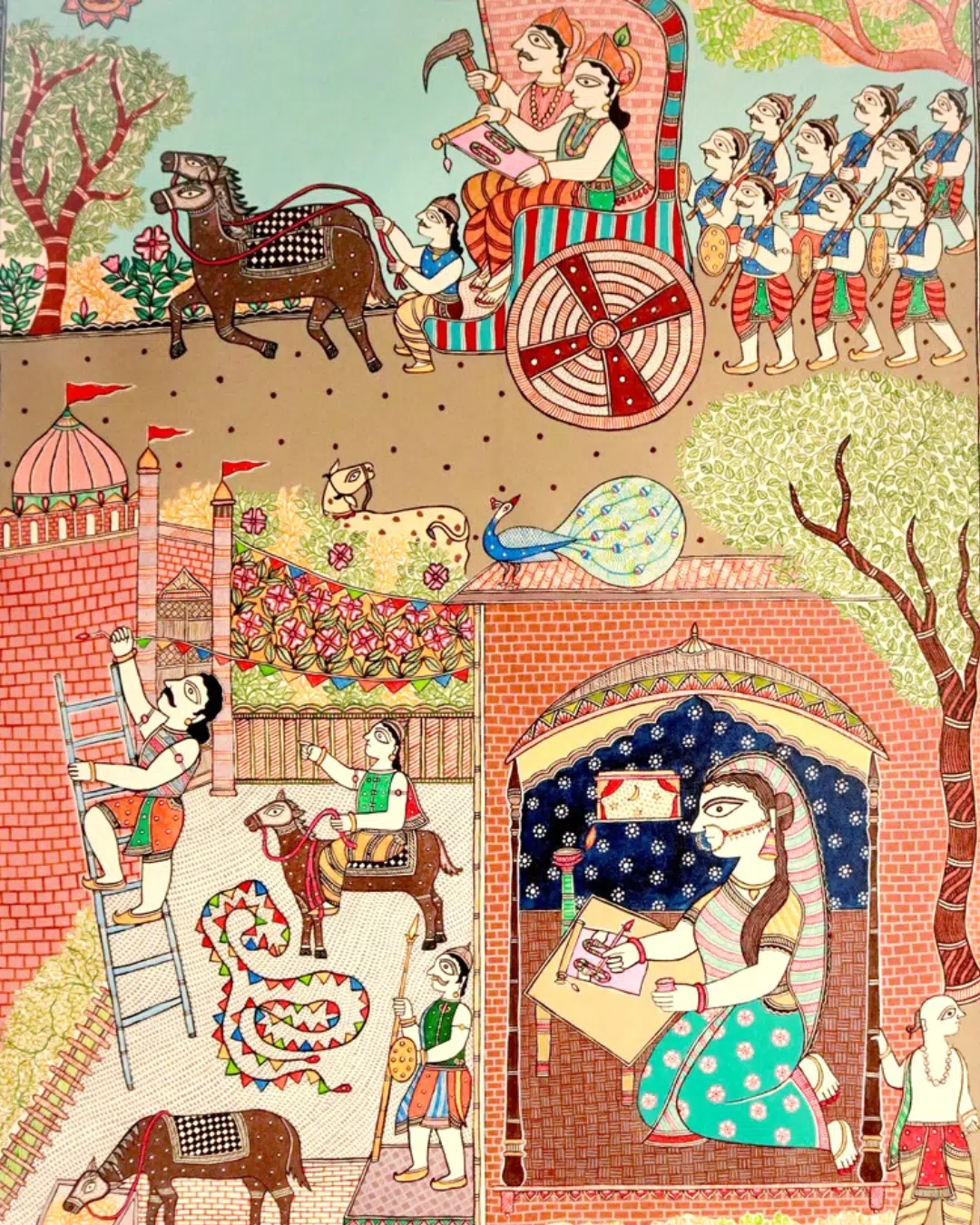

8. Avinash Karn, Madhubani

Avinash Karn. Rukmini Letter to Krishna, Year unknown. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of Artzolo.

Avinash Karn. Rukmini Letter to Krishna, Year unknown. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of Artzolo.

At just 32, Avinash Karn is one of the most exciting new names in Madhubani painting, a traditional artform also known as Mithila art because of its origins in the Mithila region of India and Nepal. Born into a family of traditional artists in the village of Ranti in Bihar, the artist draws on both traditional Madhubani motifs and contemporary pop-cultural imagery, as in his depiction of Delhi in Delhi Behrupiya Sahar that combines the classic Madhubani trees and birds with renderings of urban advertisement hoardings and tourist filled monuments. Karn’s works are dense with symbols and imagery that together represent our social reality in all its complexity. Not just an artist, Karn is also an educator with a mission to make the once caste-restricted Madhubani art form accessible to all. Since 2021, the artist has been running ArtBole, a studio in his village dedicated to helping people from marginalised communities, particularly Muslim women, tell their stories through Madhubani painting.

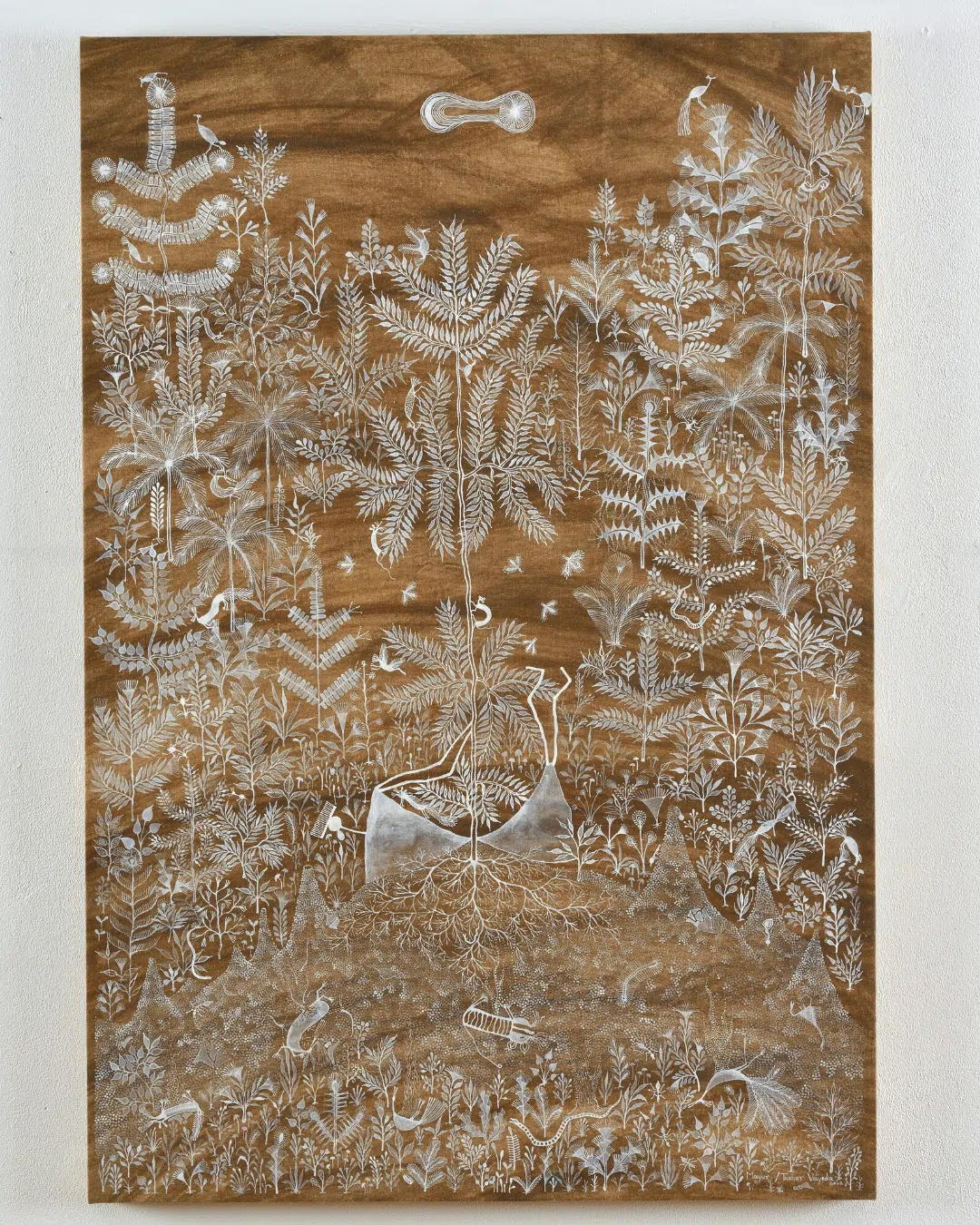

9. Tushar Vayeda and Mayur Vayeda Brothers, Warli

Vayeda Brothers. Ashes to Ashes (Rebirth), 2022. Rice paste and acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artists.

Vayeda Brothers. Ashes to Ashes (Rebirth), 2022. Rice paste and acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artists.

Born and brought up in the Warli village of Ganjad in rural Maharashtra, brothers and artists Mayur and Tushar Vayeda grew up surrounded by Warli stories, rituals and the ceremonial Warli paintings, recognisable for their geometric patterns and natural and community themes. In an effort to “bring back the history of Warli artforms practised by tribal ancestors,” the Vayeda brothers have developed a practice that stays true to the traditional materials and motifs of Warli art— creating rhythmic alphabet-like forms with white pigment on surfaces primed with contrasting reddish-brown cow dung. Simultaneously, the brothers use the centuries-old visual language to reflect on the world today, telling stories of urbanisation and natural destruction along with the myths and folktales passed down through the generations.

10. Sangita Jogi, Jogi

Sangita Jogi. The Women I Could Be, Year unknown. Off-set printed with special spot colours. Courtesy of Tara Books.

Sangita Jogi. The Women I Could Be, Year unknown. Off-set printed with special spot colours. Courtesy of Tara Books.

24 year-old Sangita Jogi practices an art form unique to her family in rural Rajasthan. ‘Jogi’ art has been practised by three generations of her family, and is characterised by narrative drawings of figures in landscapes rendered in intricate dots and dashes of black ink on white paper. Once nomadic musicians, the Jogis turned to visual art to give form to traditional songs and stories after being forced to give up music for manual labour due to industrialisation. Along with her siblings, Sangita Jogi has been innovating on the artform ever since she began drawing as a child, imbuing it with colour, movement and using it not just to reflect on the real world around her but to fabulate new lives for herself and the women around her, as can be seen in her Women Partying, a star-studded dance scene, and Women Rescuers, showing women in helicopters bringing aid to a flooded village. As the artist says, “I draw what I would like to see—empowered women enjoying life.”