Where do you work?

I moved into a studio nearly six years ago — it is near my house, has great light and ventilation, and is very economical being located in a low-income neighbourhood in Tughlakabad Extension. If you walk further down, it becomes a crazy ghetto with nearly fifteen people living under a single shed. Delhi’s planning mechanism never took care of the poor people, it never accounted for them. For this reason, they were forced to occupy unauthorised localities like these.

I don’t spend a lot of time in my studio though, as most of my work happens on the site. I don’t have any employees, and when I need people I hire them on a daily wage. However, having a separate space like this is always useful. Sometimes a lot of kids from the neighbourhood visit me, curious about what I am making, and I only confuse them further with my ambiguous replies. Once I got someone to interview my landlord who I share a good relationship with. When asked about what I do, he said “Woh scientist type ke lagte hai, kuch kuch karte rehte hai” (“He looks like a scientist and is always up to something”)!

I find myself fortunate that I didn’t study art but that I am a practising artist. I also don’t feel any compulsion to produce art for the rest of my life. When I start working on a project, I delve deep into it. But once it’s over, I do not wish to go back to it. I take long breaks which eventually feed into ideas for new projects. Altogether, I do not spend more than six months in a year on producing art. I continue to do other things — I read, sleep, travel and take care of my kids.

The artist in his New Delhi studio, 2018. Copyright India Art Fair

What inspires you?

At times, it seems a frivolous occupation: art. I find that most artists consider the creative process as something holy as though they can not help but produce art. These days, many of the students coming out of art colleges or those aspiring to be artists feel that they need to be creative for the rest of their lives. They are obsessed with doing something new and fear repeating someone else’s idea. I think that’s just too much pressure to put on one’s self. Not doing anything is also very important!

What was your most recent exhibition?

The focus of my exhibition at Nature Morte was on particular sites that have been recently altered by violence in Baghdad, Kabul, Raqqa and Aleppo. I went through a lot of academic writing on the psychology of war, mathematical analysis of experimental data, literature on planned and perceived obsolescence and compiled this research into a book. This book is about the title of the show: Residual Fear.

Let me put it this way: suppose you perform an experiment on mice with a reward on one side and a punishment on the other. Before you put the mice back to their natural environment, you are supposed to reverse that psychology, so that the conditioned fear doesn’t continue to remain in their minds after the experiment.

“Can the people or places that have witnessed organised violence for such a long period of time overcome the trauma? Is it possible for them to undo years of conditioning to embrace democracy? Can they even think about returning to normalcy after having gone through such brutalisation and fragmentation? The show sought to address some of these concerns.”

But that doesn’t always work, there is always some lingering, residual fear that is left behind. This is what I was looking at – how an experiment or an action can have a secondary reaction. You could apply this logic to regime change or spreading democracy. Can the people or places that have witnessed organised violence for such a long period of time overcome the trauma? Is it possible for them to undo years of conditioning to embrace democracy? Can they even think about returning to normalcy after having gone through such brutalisation and fragmentation? The show sought to address some of these concerns.

I am very conscious about who can view my works or access the site that they are being shown at. While some of my installations have been displayed in public spaces, this show was always meant for a gallery, which is a particular kind of space, exclusive to only a few people. There is one underlying feeling or emotion that is common to all the works: anxiety.

Tell us about a piece that was hard to create?

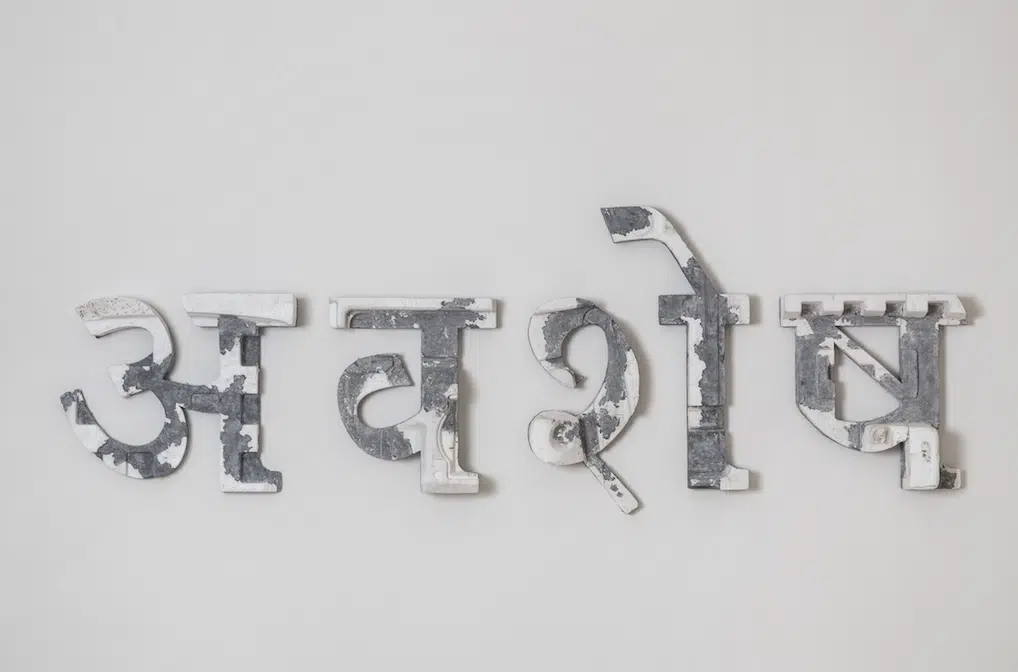

Avshesh, the piece made out of concrete and thermocol, was undoubtedly the hardest to create. I was looking at consumerism and its impact on the environment. Working with these two unsustainable yet widely-used materials was therefore a conscious choice. I wanted to use them to cast letters of a Hindi word, “Avshesh” which literally translates to “leftovers” or “scrap”. However, I had not worked with the medium before and took a great deal of time to get it right. One of the letters broke a week before the show was to open so I had to make a replacement at the last minute!

Asim Waqif. Avshesh, 2018. Courtesy of Nature Morte

What are you currently working on?

Bamboo is a locally grown material in India and I have been working with it for some time. Last year, I began working on a site specific bamboo plantation at the Sculpture Park in Sylhet, Bangladesh led by the Samdani Art Foundation. I want to manipulate the growth of the bamboo plant to create different structures and I am making aeolian whistles with the bamboo that will play according to wind conditions. I am interested in combining traditional practice with high-tech knowledge.

Born in 1978 in Hyderabad, Asim Waqif trained as an architect and worked as an art director for film and television before turning to a dedicated art practice. He works with sculpture, video, photography and, more recently, with large-scale interactive installations that combine traditional and new media technologies. He is represented by Nature Morte, and currently lives and works in New Delhi, India.