While you might be familiar with the heroes of Indian modernism — from the brotherhood of the Bengal School, to the commercially successful and male-dominated circle of Progressive painters — the real history of the movement is anything but a boys’ club. Below, we take a look at its unsung heroines: eight female twentieth-century artists who pioneered modernism on the subcontinent.

1. Amrita Sher Gil (1913 – 1941)

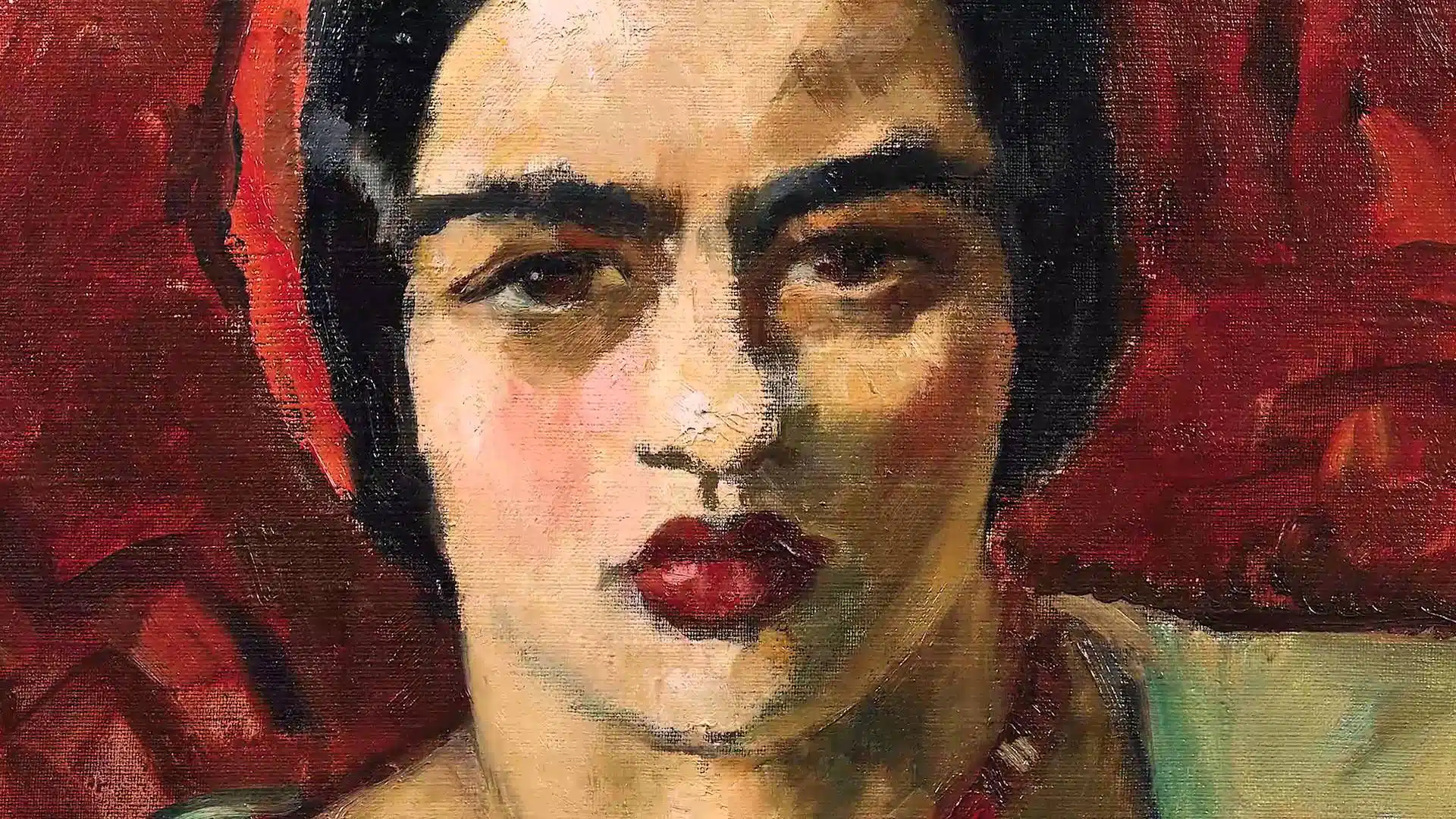

Amrita Sher Gil. Self portrait, 1931. Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Amrita Sher Gil is often affectionately described as the ‘Indian Frida Kahlo’ — an epithet that aptly takes into consideration her richly coloured paintings, many of which were self-portraits, as well as her unorthodox, bohemian lifestyle.

Like Frida, much of Amrita’s work was inspired by her cultural roots. Born to a Hungarian mother and an aristocratic Sikh father, her early years were spent navigating her bicultural identity. Although she trained in Paris, steadily gaining recognition in Europe, it was in India that her work flourished. She was inspired by Mughal and Pahari schools of painting, as well as the “frescoes” of Ajanta, which she described as being “worth more than the whole Renaissance”.

By the mid-1930s, she had found in the Indian tradition a flatter, more modern mode of expression. Despite her privileged background, her paintings vividly represent the unglamorous lives of ordinary people, stepping away from the sentimental depictions of India made by contemporary Orientalist painters.

2. B. Prabha (1933 – 2001)

B. Prabha. Untitled, 1985. Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of Artnet

Prabha began painting at a time where very few women were professional artists. She was born in the village of Bela, near Nagpur in Maharastra, and studied at the Nagpur School of Art before moving to Bombay to pursue a diploma at the Sir JJ School of Art. Inspired by Amrita Sher Gil, Prabha wanted to represent real female subjects, liberated from the gaze of the male artist. She is best known for her figurative oil paintings of “the trauma and tragedy of women” — namely, depictions of melancholy rural women in natural colour palettes.

3. Nasreen Mohamedi (1937 – 1990)

Nasreen Mohamedi. Untitled, early 1980s. Drawing on Paper. Courtesy of Chatterjee & Lal

Nasreen Mohamedi’s abstract, monochrome forms are unique for the paradoxes they seem to defy. Her line drawings — rendered with precision in combinations of ink, graphite and gouache — are soulful, rather than sterile; in spite of their structural, even architectural integrity, they are simultaneously dynamic and weightless.

Raised in post-Independence India, Mohamedi’s minimalist vocabulary was cultivated by a lifetime of both local and cosmopolitan experiences. She studied at Central St. Martin’s in London, before working at a printmaking atelier in Paris. Although she later returned to India, where she lived and worked for the rest of her life, she also drew inspiration from her extensive travels around Asia and the Middle East. Her exposure to Islamic architecture, Sufism, Zen Buddhism, textile weaving and calligraphy gave significant direction to her work, both in aesthetic and spiritual terms. Mohamedi’s work combines these influences with poetic economy, paradoxically obtaining, as she wrote in her diaries, “the maximum of the minimum”.

Even the onset of a rare neurological and motor disorder called Huntington’s Chorea did not impede the development of Mohamedi’s meticulously geometric style. Remarkably, she managed to continue working with her drawing hand, experimenting further with dimension, line, and shape.

4. Arpita Singh (1937 –)

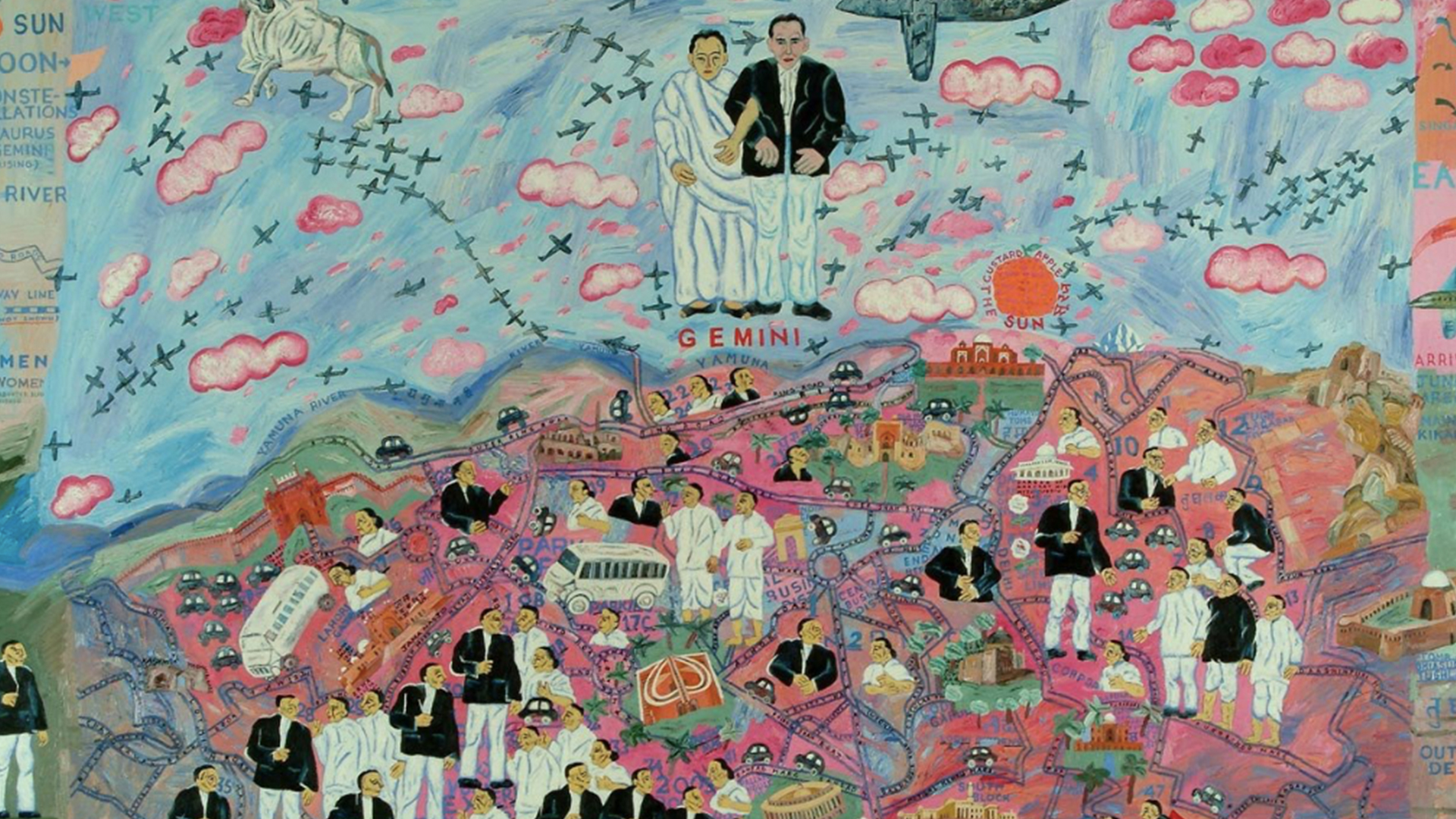

Arpita Singh. My Lollipop City, 2005. Screen print. Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery

Arpita Singh’s paintings teem with life. Populated with the forms of people, animals, trees and flowers — as well as recurring motifs from urban life, such as guns, cars, and planes — her works create microcosms, or little worlds, in which ideas and objects interact, find connections, and acquire new meanings.

These qualities of detail, story-telling and minuteness all draw on traditional Indian aesthetics. Alongside the influence of Mughal miniaturist painting, Singh has been inspired by her own Bengali heritage: kantha embroidery, Kalighat scrolls, and other folk-art practices. Singh, née Dutta, spent most of her childhood in pre-partition West Bengal, but has since lived and worked in Delhi. Her employment at the Weaver’s Service Centres of Kolkata and New Delhi in the 1960s, where she became immersed in the traditional techniques pan-Indian art forms, has had a marked impact on her highly individualistic style.

5. Nilima Sheikh (1945 –)

Nilima Sheikh. Nasreen at Tithal Beach, 2015. Mixed tempera on sanganer paper. Courtesy of Artsy

Like Arpita Singh, who she worked with as part of an artistic collective, Baroda-based artist Nilima Sheikh has created a unique visual language for her pictorial narratives, based on traditions of heritage art. Before she received an Masters in Fine Arts from MSU Baroda in 1971, where she was taught by the renowned artist K.G. Subramanyan, Sheikh studied history at Delhi University. This academic background is the foundation of her artwork, which draws comparisons between ancient and modern history. Themes such as displacement and patriarchal violence are handled in her oeuvre by way of poetry, folk narrative and Sufi mysticism. From 2002 onwards, Sheikh’s work has dealt primarily with India’s turbulent political climate. She has taken both the Gujarat riots and the struggles of the Kashmir valley as her subject matter, outlining cartographies of grief and violence. In the 1980s, Sheikh was also an outspoken conservationist of artistic heritage. The longstanding influence of forms such as picchwai painting on her style is evident.

6. Nalini Malani (1946 –)

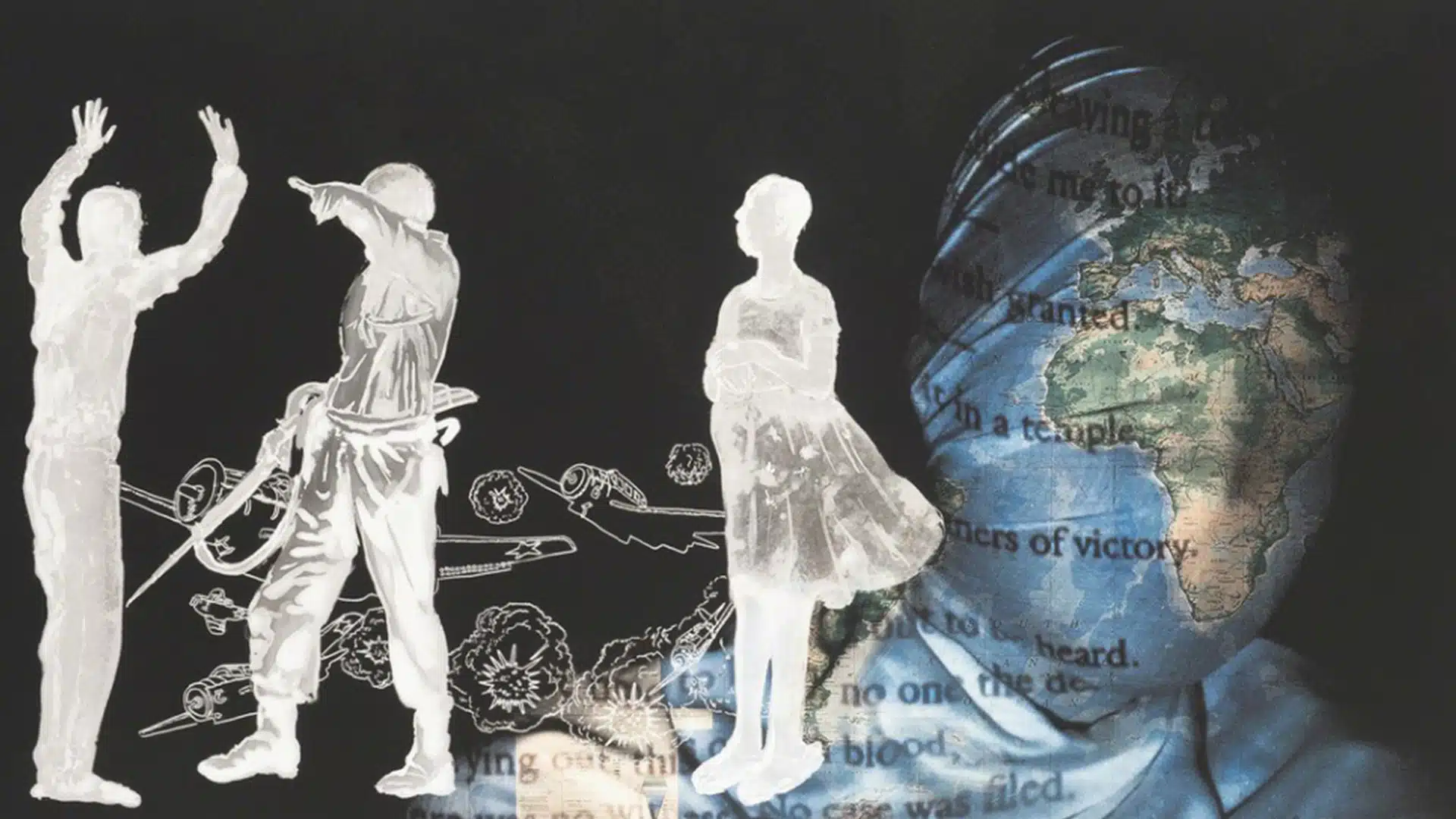

Nalini Malani. This is Africa, 2005. Digital Print. Courtesy of Artsy

Nalini Malani’s art practice has been unquestionably shaped by her upbringing during the aftermath of the Partition. Although she was born in Karachi, she has lived almost her entire life in India — first as a refugee in Calcutta, and later in Bombay, where she studied Fine Art at the prestigious Sir JJ School of Art. Her work thus explores themes such as memory, trauma, resistance, gendered violence, and mythology, often through the theoretical lens of feminism.

Malani has also been a central force in ushering both Indian and global art into a contemporary idiom. Maintaining her preoccupation with modernist ideas, her work since the 1980s has been playful in terms of medium and technique. She is now most widely celebrated for her experiments with reverse painting, film, shadow theatres, ephemeral murals and performance.

As a true trailblazer and feminist, Malani organised India’s first all-women artists’ show in 1985. She was also the first Asian woman to receive the Arts & Culture Fukuoka Prize in 2013, recognised by the committee as one of the world’s most influential living artists.

7. Madhvi Parekh (1942 –)

Madhvi Parekh. Playing with Animal, 1989. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of DAG

Born in Sanjaya, Gujarat, Madhvi Parekh’s work underscores the rich heritage of folk traditions, such as embroidery and picchwai painting. Parekh’s lushly-coloured and deceptively simple paintings reflect her preoccupation with childhood and the poetics of everyday rural life, also inspired by a range of Western influences, from Paul Klee to Henri Matisse. Her work, however, refuses to reconcile this tension between the vernacular and the modern; instead, the artist’s uses her unique visual vocabulary to raise questions about how to interpret the folkloric in a modern India. Her magical, playful paintings draw from memory, as well as from both Hindu and Christian religious artwork.

8. Mrinalini Mukherjee (1949 – 2017)

Mrinalini Mukherjee. Bouquet, 2013. Bronze. Courtesy of Nature Morte

The only sculptor on this list, Mrinalini Mukherjee had a childhood unlike any of her contemporaries. As the daughter of distinguished artist Benode Behari Mukherjee, she was raised in Santiniketan in Bengal, at the heart of India’s modernist intellectual and artistic community. She then went on to study mural painting at MSU in Baroda, where, like Nilima Sheikh, she worked under K.G. Subramanyan.

Subramanyan’s mentorship was crucial to Mukherjee’s development, and encouraged by his celebration of vernacular Indian craft traditions, she began sculpting with natural fibres. This sparked her use of modest artisanal materials such as jute, rope, bronze, textiles and ceramic to create ‘high art’: complex, even erotic, organic forms made by knotting, weaving, hammering, and moulding.