Naeem Mohaiemen works in Dhaka and New York, combining film, installations, and essays to investigate incomplete decolonisations and the erasing of political utopias. Here, he shares a reading list on Bengali history, including novels now available in English translation.

1. Joya Chatterji, Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947

After 25 years, this is still one of the most thorough analyses of the root causes of Partition. Chatterji goes beyond the typical explanations which emphasise British intrigue, national factions, and the escalating violence around 1947. Instead, she reaches back to the first partition of Bengal in 1905 and then traces how the politics of the Hindu bhadralok class ossified around land ownership that excluded Muslims and lower-caste Hindus. Long before the horror of riots, the 1932 Macdonald’s Communal Award and the Poona Pact dramatically altered the balance of power. It became clear that, in a united Bengal, the bhadralok class would face reduced political power as a rising Muslim middle and peasant class became newly enfranchised. The Partition of Bengal became “inevitable” as a result of a toxic mixture of entrenched privileges that could only be preserved in “Bengal divided”.

2. Akhteruzzaman Elias, Khoabnama [Chronicle of Dreams], 1996

Since his very early death at age 53, Elias’s handful of books have acquired totemic quality, and none more so than his magnum opus Khoabnama. Set in Bengal before the 1947 Partition of India, it sketches a grand narrative on a small scale. The book is set in a wetland in North Bengal, where the ghosts of the 18th century Fakir-Sannyasi Rebellion keep appearing to a fisherman. When the just society promised by the creation of Pakistan fails to arrive, the fisherman’s son joins the communist-inspired Tebhaga Movement. Elias writes the novel in a dense, headlong, modernist prose style that has hardly any parallel among his contemporaries. The slippage between the voices of the spirits and humans remind me of the farishta (angel) dialogues in Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses (1988), though the device is put to radically different use here. Khoabnama will finally appear in English translation in 2020.

3. Shaheen Akhtar, Taalash [The Search], 2004

Akhtar’s second novel is an exemplar of taking a research project, whose public face encompassed many contradictions, and working out its tangled threads through the freedoms of fiction. In the 1990s, the feminist legal aid organisation Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK) pioneered an oral history of the 1971 Bangladesh War, documenting cases of women who were sexually assaulted by the Pakistan army during the war. Placing survivors on a public stage was a contested move, as later documented in Nayanika Mookherjee’s The Spectral Wound (2015). Akhtar was part of ASK’s team of researchers, and this novel has a researcher navigating the waters of traumatic memory, including the ostracism of victims by the Bengali side after the war. The complex position of one key survivor and witness, who has been represented as herself and fictionalised in multiple books and films, continues to trouble this terrain today. This novel is a rare attempt at reckoning with the brutalisation of women in times of war and peace.

4. Mahmudul Haque, Kalo Borof [Black Ice], 1977

The element that closely ties together the late novelist Mahmudul Haque and his translator Mahmud Rahman is a resolute, and atypical, lack of sentimentalism around the 1971 Bangladesh War. Rahman is the author of a collection of short stories Killing the Water (2010) which displays a brutal honesty around the war that also typifies Haque’s work. Black Ice is an excellent example, centering around the life of a village teacher in a newly independent Bangladesh. The novel begins with the teacher recalling his memories of pre-1947 Kolkata (paralleling Haque’s own life), but by the end, the disappointment of independence spills over into the bitter relationship between the teacher and his wife. Haque’s refusal to follow the standard nationalist line, and his insistence on complicating both pre-1947 Bengal and post-1947 Pakistan, did not make him a popular literary figure. By his forties, he had stopped writing entirely and delved into mysticism. Rahman discovered Haque’s work only a year before his death. This late bond between the two men resulted in this rare and brilliant translation.

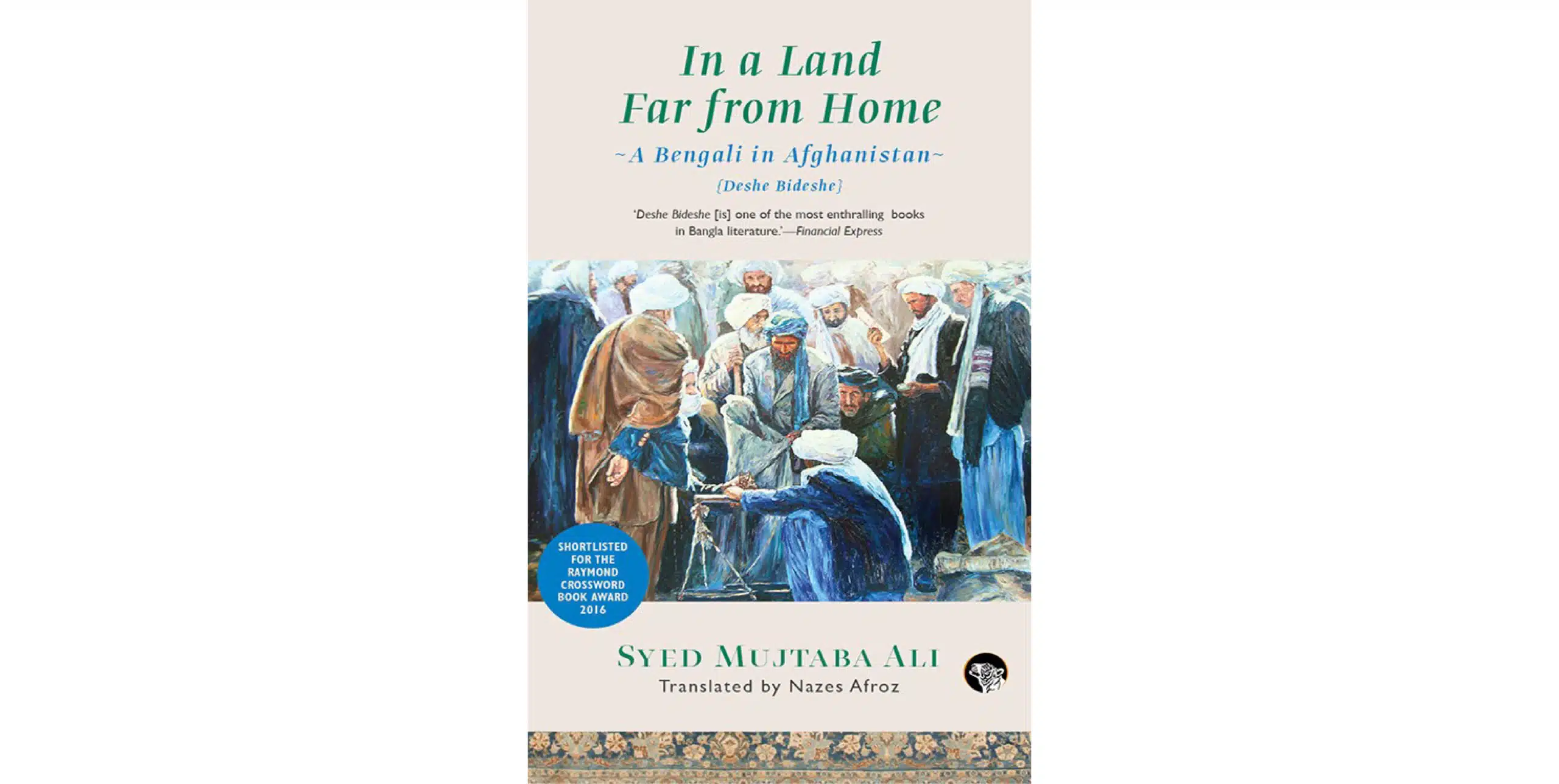

5. Syed Mujtaba Ali, Deshe Bideshe [In a Land Far from Home], 1948

I end with my great uncle Syed Mujtaba Ali. A novelist and raconteur, he was rendered spiritually bereft by the 1947 Partition, and spent many years in Kolkata, far from his family in East Bengal. Though his European travels are widely quoted, and I have translated an account of his Italian and French sojourns, it is this story of Afghanistan that was his first and most popular book. Preternaturally gifted at languages, he was sent to Kabul Agricultural College to teach Persian and English after he finished his studies at Santiniketan. While many humorous elements that reappear in his later travel stories are already present here, including the faithful manservant who alternates between moments of comedy and pathos, the real reveal for me are the signs of the ‘great game’ being played out in Afghanistan between 1927 and 1929. Bandits and royals battle, while British diplomats and Russian officers plan intrigues.

Naeem Mohaiemen received helpful insights from novelist Shabnam Nadiya on Shaheen Akhtar’s work. His last solo show — dui at Experimenter, Kolkata — explored the 1947 Partition of Bengal.