Krishen Khanna’s living room is bathed in light. He’s seated on a sofa. As ever, he is excited to have an audience. Now in his nineties, his body is fragile but the sharpness of his memory gives him the authority of a storyteller. Whether within the privacy of his home, or the very public space of an opening, his listeners find themselves spellbound.

Khanna has an anecdote about every artist. Many of the stories he told me corroborated what I heard from A. Ramachandran, Akbar Padamsee and Himmat Shah during my recent visits to their studios. He is quick to recollect an incident from some 15 or 20 years ago where he stepped in to resolve an argument about unpaid rent between Himmat Shah and a government officer. Shah had asked Khanna if he could help. “So I went over there and threw my weight around,” says Khanna. He was asked by the officer if he could guarantee that Shah would pay his rent. “I said yes. I signed whatever he wanted me to and said, ‘he [Shah] will pay in stages, what is wrong with that?’. I have a financial background as I worked in a bank, you see. And he understood that.”

“I have one long sitting, from nine in the evening to three in the morning. I don’t build up my pictures from preliminary sketches. I work straight on the canvas. When I smear the base paint, I make the first contact with the canvas and the image grows from there. Painting is all about image making.”

Because he spent many years as a banker at Grindlays, Khanna was often referred to as the “banker-painter”. In a profile of the artist written in 1957 in The Statesman, Richard Bartholomew refers to him as such, qualifying him as a man of many tastes who “manages to salvage the time necessary to be a full-time painter, despite the fact that he works in a bank in Madras.” Khanna had told Bartholomew about his strategy, which involved painting at night. “I have one long sitting, from nine in the evening to three in the morning. I don’t build up my pictures from preliminary sketches. I work straight on the canvas. When I smear the base paint, I make the first contact with the canvas and the image grows from there. Painting is all about image making.”

As we chat over coffee, his wife, Renu, joins us. The couple met as children in Lahore. “I was seven and she was five,” Khanna says. They had the same caretaker whom they recall had announced that the two would get married someday. “His father and my father were teaching at the same college in Lahore,” Renu remembers. “Her father taught Philosophy and Psychology, and she went to London to study the same subjects,” Khanna says proudly. “She actually worked as a psychologist there, and later in Manchester and Bombay. For 22 years she has been teaching,” he points out. The artist remembers a time when Renu was on the boat to England to go to university. “I was offered a job by an advertising firm in Bombay, and I wrote to her while she was still on the ship, asking ‘I got this job, should I take it?’ She sent me a message saying, ‘No! Don’t take it, because advertising is not your calling’”.

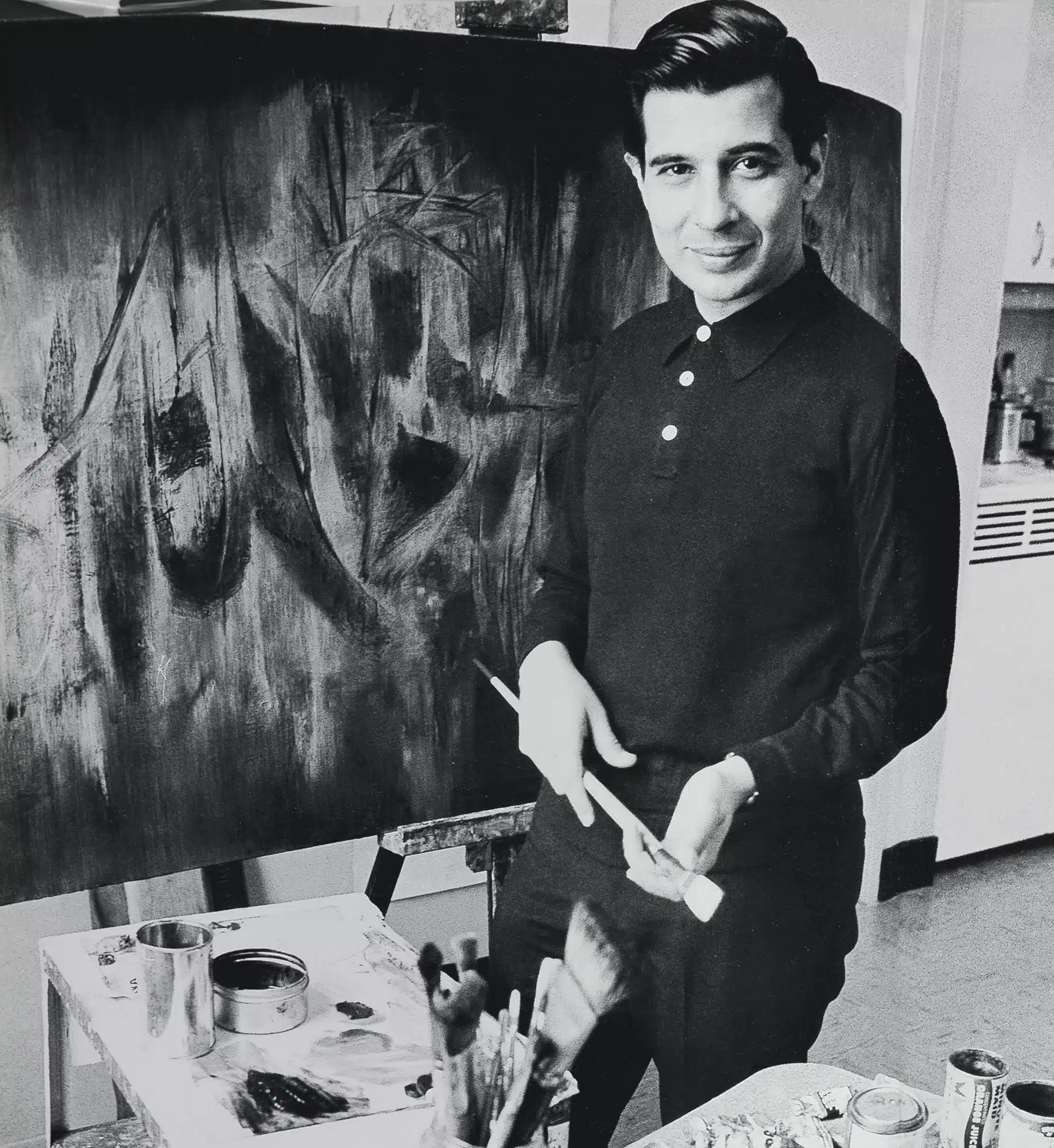

A portrait of the artist, year unknown. Courtesy of DAG

The two struggle to remember the year they got married. “It was 1952, I think,” Renu says. Khanna is not convinced. “No, 1950. And we got married in Simla. This painting that I’m currently working on is a scene from the festivities,” Khanna adds. I ask if Renu has often given him feedback on his work. “Oh yes, of course she does,” he replies. “I appreciate his work very much, and I like it a lot,” she says.

When Khanna finally leads me downstairs to his basement studio, I marvel at all the memorabilia — the scholia, fragments of photographs, cases of single malt whiskey repurposed to store brushes, and other paraphernalia. There are bottles filled with chipped-off paint that Khanna intends to display as a form of installation. I also see a desk cluttered with files. He says that they contain all his correspondence with members of the Progressive Artists’ Group, and that he finally has found someone to catalogue them.

“Now in his nineties, his body is fragile but the sharpness of his memory gives him the authority of a storyteller”

In another corner of the room, the light strains in from slats in the window. I behold the painting he’d been speaking about all afternoon. It is indeed a fragment of a memory, reminiscing about the day that he and Renu got married. He looks at it lovingly. More than two hours have passed since I arrived. He asks if we can go back upstairs, as he is getting tired. I sense that this is my cue to leave. I escort him back to where Renu is sitting.

“Wait, stay for a little bit longer,” he says. “Have I told you about the work I want to do with the photographic negatives?” And just like that, he baits me. Another hour passes. After leaving it strikes me that once he quit his full-time job, he exchanged the title of “banker-artist” for a more fulfilling replacement: that of a legendary storyteller.

Born in 1925, Krishen Khanna is one of India’s finest living modern artists. He is the recipient of several prestigious awards, including the Padma Shri and Lalit Kala Ratna. He is represented by Vadehra Art Gallery and has shown at India Art Fair in previous years.