Her practice is attuned to invisible infrastructures—root systems, mycelial networks, data flows—that quietly sustain concrete, steel, and everyday life. Drawing from tactile encounters with the city, Shreni digitally reconstitutes textures of found materials, using technology as a tool to meditate on interdependence, resilience, and memory.

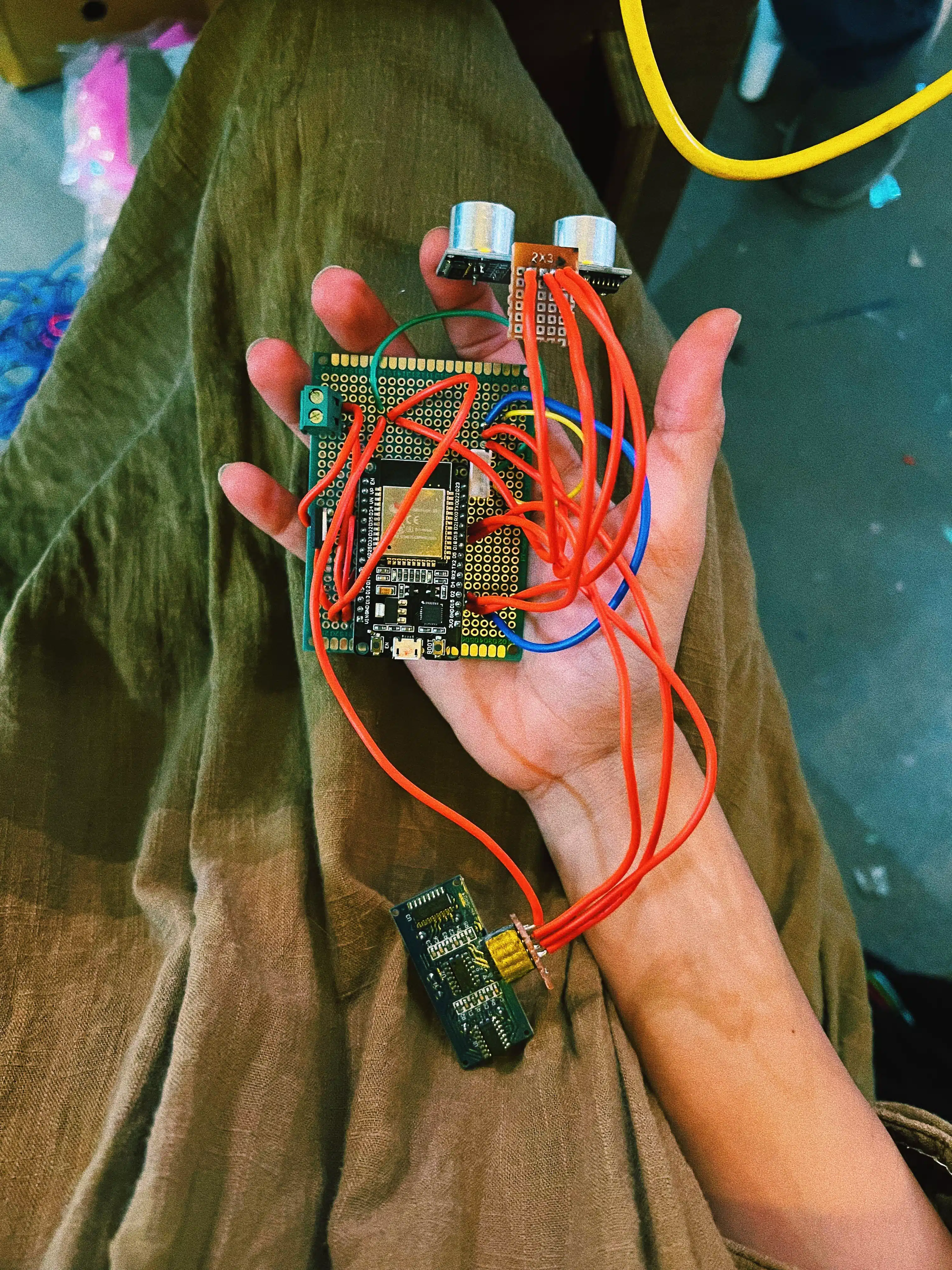

Her studio operates as a fluid, research-led space—one that allows for fabricating, foraging, and prototyping. “My work requires digital precision, so I submerge myself in the process until the logic of the piece reveals itself,” she says. Rituals anchor her days: meditation, writing, coffee, and long walks by the sea in Bandra. “I protect my mornings. In a city this loud, silence becomes a material I have to actively generate.”

Trained in design, a large part of her process involves unlearning perfection and learning to surrender and let go while creating art. Instead of manually modelling every pixel into the software, she allows data to dictate the growth of the digital organism. She intentionally imbues her work with an element of randomness by reproducing it through technology. She further elucidates by saying, “I read that dust is the ultimate archive of time. So instead of cleaning my work, I let it gather dust. By adding noise, grain, and randomness, time and nature become co-creators in my work. That shift from seeking perfection to archiving decay is where my practice lives now.”

“I protect my mornings. In a city this loud, silence is a material that I have to actively generate”

A pivotal moment that shapes her practice involves a trip to a forest in South India along with scientists who spoke about the architecture of survival– how plants choose their roots, and the role of mycelium in enabling the process. To her, this phenomenon is a fitting metaphor for the city (Mumbai) that relies on invisible communities to sustain its people. She digs past the concrete and maps entanglement to reveal the systems underneath and uses technology to hold the contradictions of the biological and the digital, the ancient and the futuristic. Shreni is curious to find out if a machine can learn to breathe, or if a pixel can carry the emotional weight of a memory. She forages ‘invisible’ data points of the city, such as, fragments of sound, textures of moss on a wall, or rhythms of a shadow, and distils them into a sensation of that moment. This gives a fleeting and static observation, a nervous system that evolves onscreen.

“I am interested in resilience, specifically, the quiet and stubborn kind found in the cracks of the city,” she says, to emphasise her fascination with the fervour of the smallest living organisms in adapting to stay alive and grow. From a root forcing its way through concrete to a digital memory trying to survive in a decaying hard drive, she is interested in the physics of perception. She studies how light, from the sun or a projector, can change the emotional weight of a space. She also seeks to construct moments of stillness that force the viewer to pause from the constant everyday running, echoing her rituals of meditation and practising stillness.

“I am interested in resilience, specifically, the quiet and stubborn kind found in the cracks of the city,” she says, to emphasise her fascination with the fervour of the smallest living organisms in adapting to stay alive and grow. From a root forcing its way through concrete to a digital memory trying to survive in a decaying hard drive, she is interested in the physics of perception. She studies how light, from the sun or a projector, can change the emotional weight of a space. She also seeks to construct moments of stillness that force the viewer to pause from the constant everyday running, echoing her rituals of meditation and practising stillness.

From a root forcing its way through concrete to a digital memory trying to survive in a decaying hard drive, she is interested in the physics of perception.

At India Art Fair, Shreni will show a large-scale video installation that acts as a time capsule. Oriented towards process rather than a finished output, she will employ three-dimensional visualisations to cultivate a root system that functions as a memory bank. “I’m not just building an image, I’m attempting to simulate the sensation of what it looks like when a city remembers. It is a process of translation,” she beams and continues to ask, “We spend so much of our lives looking at screens. But what happens when the screen looks back? Or when an installation moves, breathes, or reacts to presence? These occurrences shift the dynamic from observation to companionship.” Shreni’s work is a presence that shares space with its viewers in a synchronous rhythm. It purges the cold and distant perception of technology and reveals the overlaps and connections that living beings share with the digital world. She concludes by saying, “Art helps me make sense of the world– to give a shape to feelings and emotions, so with each artwork that finishes, it successively fills me with hope.”

DOWNLOAD A SPECIAL ARTIST POSTER >

Shreni was born in 1992, Mumbai, India. She is an Artist-in-Residence at India Art Fair, and her final work will be revealed at the Fair in 2026.