Born in Goa and based in Mumbai for many years, textile-artist Mayuri Chari has recently set up a new studio space in Kolhapur in rural Maharashtra, among sugarcane fields and many kilometres away from any town or city. Here, her life as an artist is tied with her domestic life and role as a daughter-in-law. Without typical Indian middle-class urban comforts such as “Swiggy or Zomato”, food and grocery delivery mobile apps, the artist’s day starts at 6 AM in the morning — “I make tea for my father-in-law, who goes on a walk in the morning and then clean the house, before preparing for lunch at 11. Half of my day goes in doing the housework.” Only after this does Chari get a chance to begin her studio work. “It was hard to adjust to my new life. Maine jwari chi bhakari toh jhak mar ke seekhi,” Chari shares, laughing about having to learn traditional Maharashtrian dishes in her new home, away from Goan fish and coconut curries. Chari talks about this life in a matter-of-fact way, as the basic truths of her reality, a reality that she shares with many women in India — “My work celebrates women, and my narration always focuses on the real — real society, real people, real stories,” she says.

DOWNLOAD A SPECIAL ARTIST POSTER >

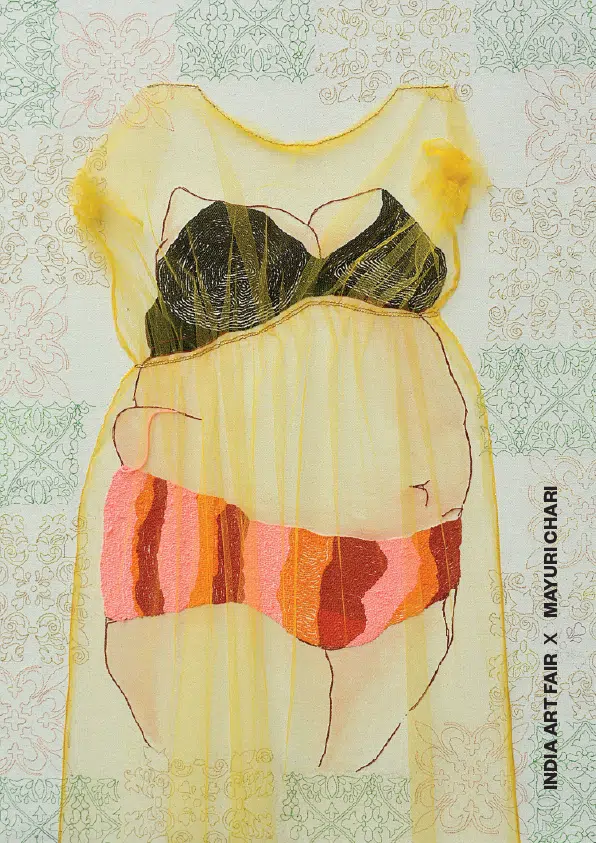

Chari’s celebration of womanhood and her feminism emerges from this interest in the basic and daily realities of the people around her. “In college, I ran a survey in my all girls hostel about sex and nudity, and was shocked by how taboo this was considered even by my peers,” the artist shares. “So, I wrote some poems about the vagina, and stitched them on a huge piece of cloth.” Having experienced the pain of the strict silence around the vagina and female body from a young age — “when I first got my period in the 7th grade, I was put in a dark corner of the house and away from any other people. I was so terrified of the dark and couldn’t sleep. Sounds from the outside would make me feel crazy” — for Chari, speaking about, writing about and recording her experiences of menstruation in thread on cloth was a way of breaking the silence for good. This origin story formed the crux of Chari’s practice and she continues to use poetry dedicated to women’s liberation, along with representations of her own body and other feminine bodies, in her art.

“My work celebrates women, and my narration always focuses on the real — real society, real people, real stories.”

“During summer holidays, my ai [mother] used to teach me how to stitch and cook so that I would become a good daughter-in-law,” Chari says, describing the beginnings of her journey as an embroidery artist. “And when I finished my Master’s degree at the Hyderabad Central University in 2017, I couldn’t afford anything other than cotton cloth and black thread, so embroidery became my medium. Even now when my ai phones me, she gives me advice on how to stitch,” the artist laughs. Chari’s use of embroidery to enact a feminist liberatory politics seeks to subvert the original effect of domestic work. Further, the act of stitching is not only a sign of protest for Chari but also of pleasure. When asked what was preoccupying her currently, she says, “mujhe stitching me bohot maza aa raha hai,” affirming her deep love for the medium.

“I get my inspiration from daily life and observations,” the artist emphasises. “I don’t pre-plan any of my work, and the work emerges as I am making it.” The idea for a series of ‘vaginas’ made of crumpled paper cups came from noticing a stained and used chai cup thrown in the streets, a metonym for the way in which feminine bodies are judged for their “unevennesses” for the artist. An encounter with women making dung fuel cakes in a neighbouring village led to the creation of another series of ‘vagina’ artworks, this time made with cow dung. “The impressions of the womens’ fingers in the dung and the imperfections of the forms reminded me of the layers of the vagina,” says Chari. The work also took the form of a performance in which she involved a group of school children in making the cow dung ‘vaginas’ with her. “The boys were embarrassed but the girls really got curious and started sharing experiences of menstruation with me,” says Chari. “And all their forms were so totally different from mine.”

The portable sewing machine is the primary tool in Mayuri Chari’s practice. Courtesy of the artist.

The vagina is not a monolith for the artist, but instead an organ and concept that exists in multivarious forms — in the end, simply a stand-in for the societal rejection of the feminine as impure and prohibited. In making multiple series of multiple vaginas, the artist takes into account the way in which a woman’s experience can differ widely on the basis of her caste, class and religion. Caste discrimination is of particular interest to the artist — having been cast aside by her family after entering into an inter-caste marriage — not only speaking of liberation from the “chains of caste” in her embroidered poems but also by thinking through notions purity and impurity across her works, concepts which also structure caste hierarchy.

Chari is currently working on several projects centred on the manual labourers who work in the sugarcane fields and brick kilns in her area, including a film and textile drawings. Along with her partner and fellow artist, Prabhakar Kamble, she plans to expand their studio space into a residency and art space for the community.

Mayuri Chari was born in Goa in 1991, and currently lives in Kolhapur, Maharashtra. Her work will be shown at India Art Fair 2024 as part of its Artists in Residence programme.