Arpita Akhanda describes herself as a “memory collector”. As one, she explores the present through the historical past in a practice spanning paper weaves, performances, installations, drawings and video. “My grandfather migrated from Bangladesh to India before the partition in 1947,” says the artist, opening up about her own personal history and how the personal family stories of the Partition influence her work.

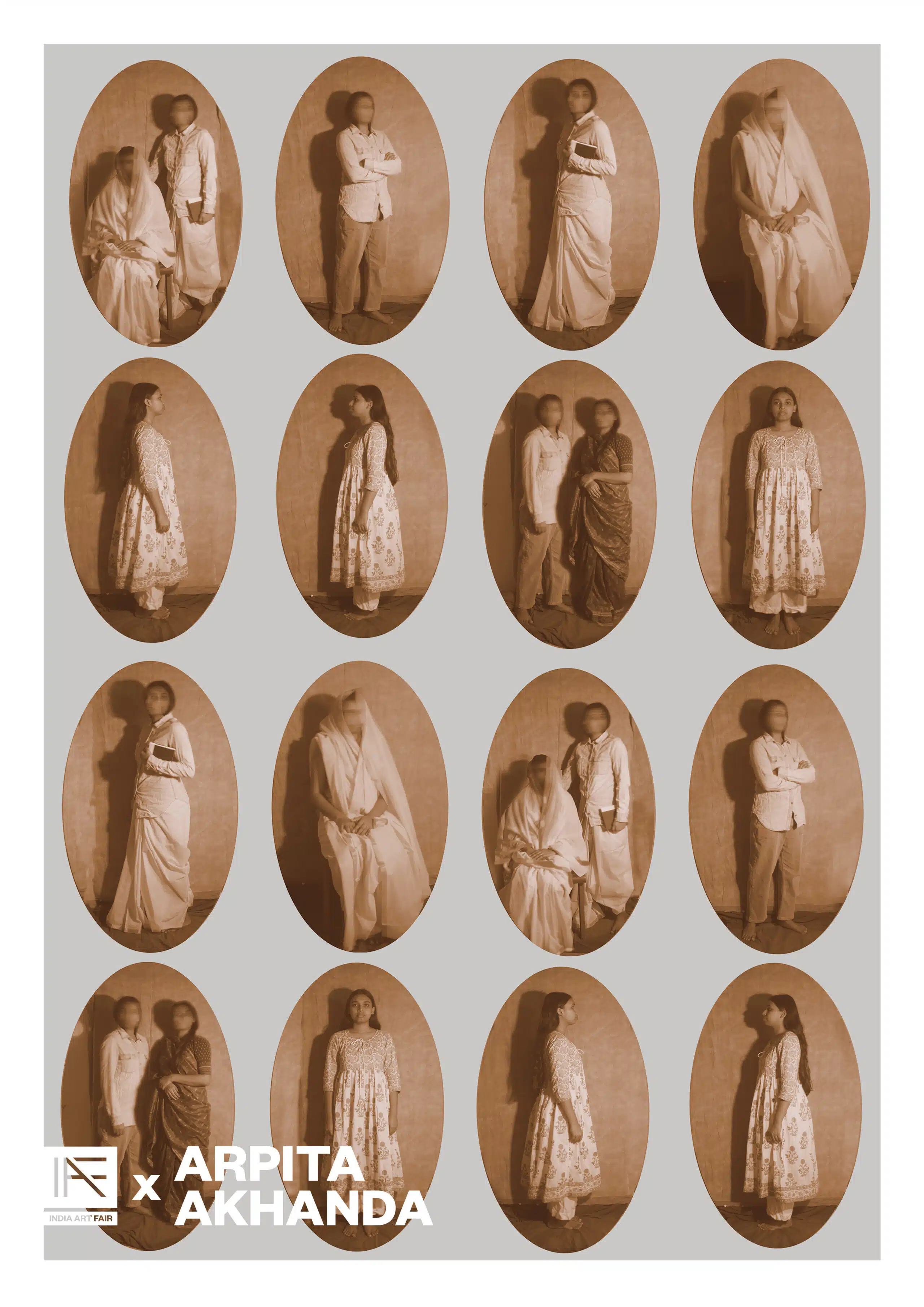

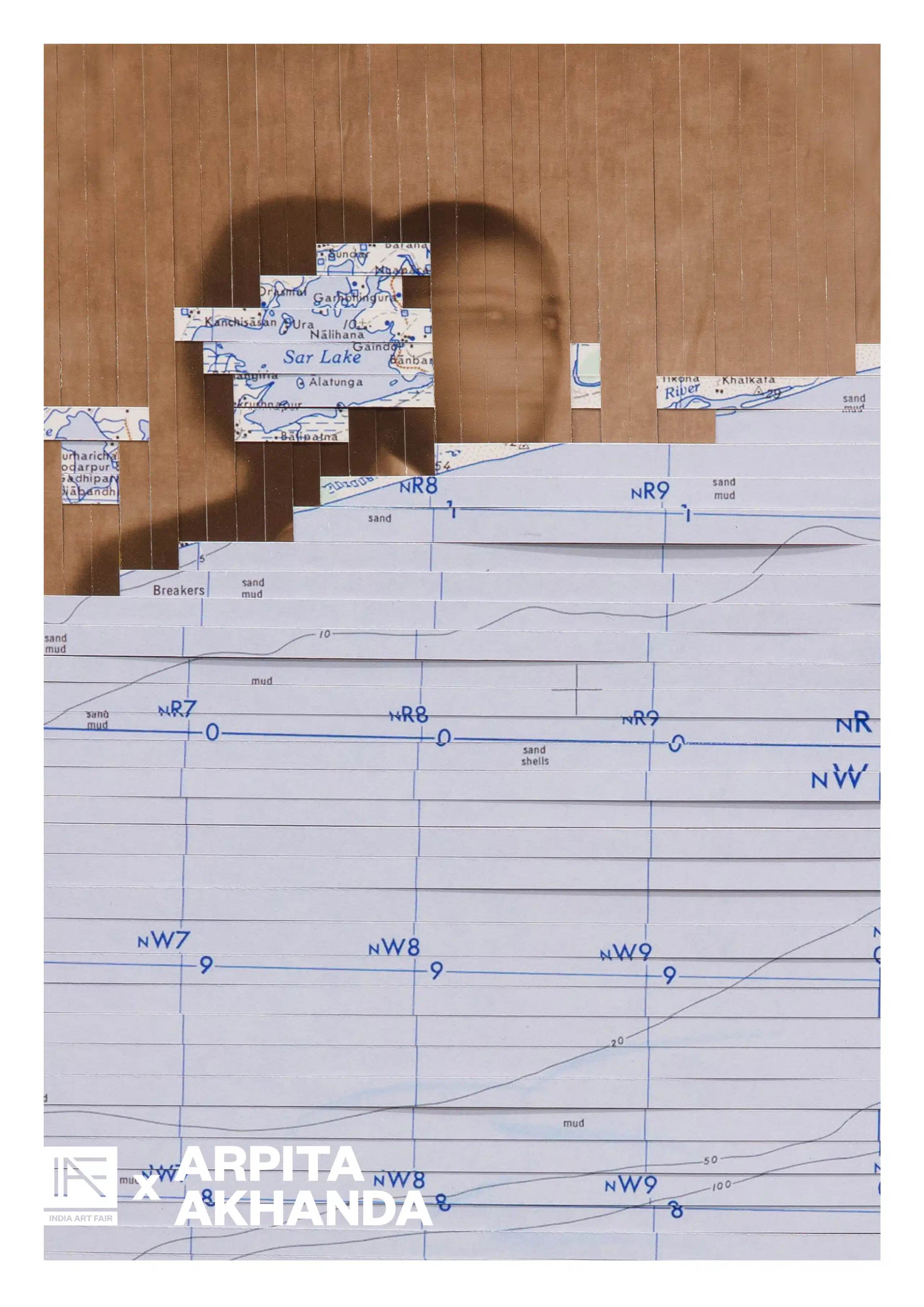

For Akhanda, documents like photographs, maps, letters, postcards — many from archives kept by her parents and grandparents — are building blocks of her art. Not just on paper, Akhanda involves her body in asking questions of culture, politics and a postcolonial identity through performance.

“I am deeply interested in personal histories, which tend to get diluted when placed next to the more institutional forms of history. It struggles to find a voice, a paragraph or any recognition.

“My practice emerges out of the personal need to decolonize memories,” the artist tells us. “I am deeply interested in personal histories, which tend to get diluted when placed next to the more institutional forms of history. It struggles to find a voice, a paragraph or any recognition. My work is to bring personal and institutional memory together, at the same footing, and to see what this can show us.”

For Akhanda, memory-collecting is an everyday practice. “I start my day by checking the news, and before beginning a piece, I like to go through all the materials I have collected, spread them on the floor, sometimes including older work,” she says describing her routine. She painstakingly documents her ideas and responses to her own work, using breakthrough moments as points of emergence for new understandings. “I believe that one piece leads to the next, so I try to carry the energy forward, travelling through its residues.”

Download artist posters here >

Akhanda lives and works in Shantiniketan, one of India’s oldest and most generative artist communities, where her studio operates like “a perceptual laboratory, a space where I constantly evolve.” Her works do not have definite origin moments and end-points, but operate rather like “chain reactions where one breakthrough moment leads to the next.”

Akhanda lives and works in Shantiniketan, one of India’s oldest and most generative artist communities, where her studio operates like “a perceptual laboratory, a space where I constantly evolve.” Her works do not have definite origin moments and end-points, but operate rather like “chain reactions where one breakthrough moment leads to the next.”

When asked about her influences, she opens up about Taiwanese-American performance artist Tehching Hsieh’s understanding of art, Indian print and visual artist Zarina Hashmi‘s way of looking at memories and Serbian conceptual artist Marina Abramović‘s philosophy of the body are all deeply influential for Akhanda, and find resonance in her work. “I like to read and research during the day,” she says while describing her relationship with the artists she loves. “And when the world around me sleeps, I concentrate on developing my own ideas and processes.”

“Shantiniketan, with its lush greenery, gentle slopes and streams, gives me the space to work in peace while being connected to my surroundings.”

In her Shantiniketan studio, nature and history go hand-in-hand. “Shantiniketan, with its lush greenery, gentle slopes and streams, gives me the space to work in peace while being connected to my surroundings,” says Akhanda, adding, “Here I constantly re-evaluate my presence and am driven deeper into my roots.” The investment in nature continues in her upcoming work in which she explores the relationship between the river and body and the way in which moving rivers become carriers of migration flows, stories and settlements.

Arpita Akhanda works at her apartment-studio in Shantiniketan in West Bengal, India. Her artist poster features excerpts from her recent performative photographic series exploring the relationship between a river and body.