Down a quiet lane inside Kaladham, a residential colony exclusively for artists in Noida—past a low white wall and a garden slipping through metal bars—we descend into a basement where Shailesh BR works. It is part workshop, part laboratory, and part carefully cultivated chaos.

The first thing we see is his work Swayamvara—the long, wall-mounted garlanding machine now almost synonymous with his practice. A marigold garland attached to a conveyor, the sculpture asks a series of questions about belief, moral obligations and family, based on which the machine ‘decides’ whether to accept your proposal of marriage—with a garland dropped ceremoniously over your head—or to reject it, prompting you to try again. The work drags the ancient idea of the swayamvara into the present: who chooses, who decides, and how much of this ‘choice’ is simply performance?

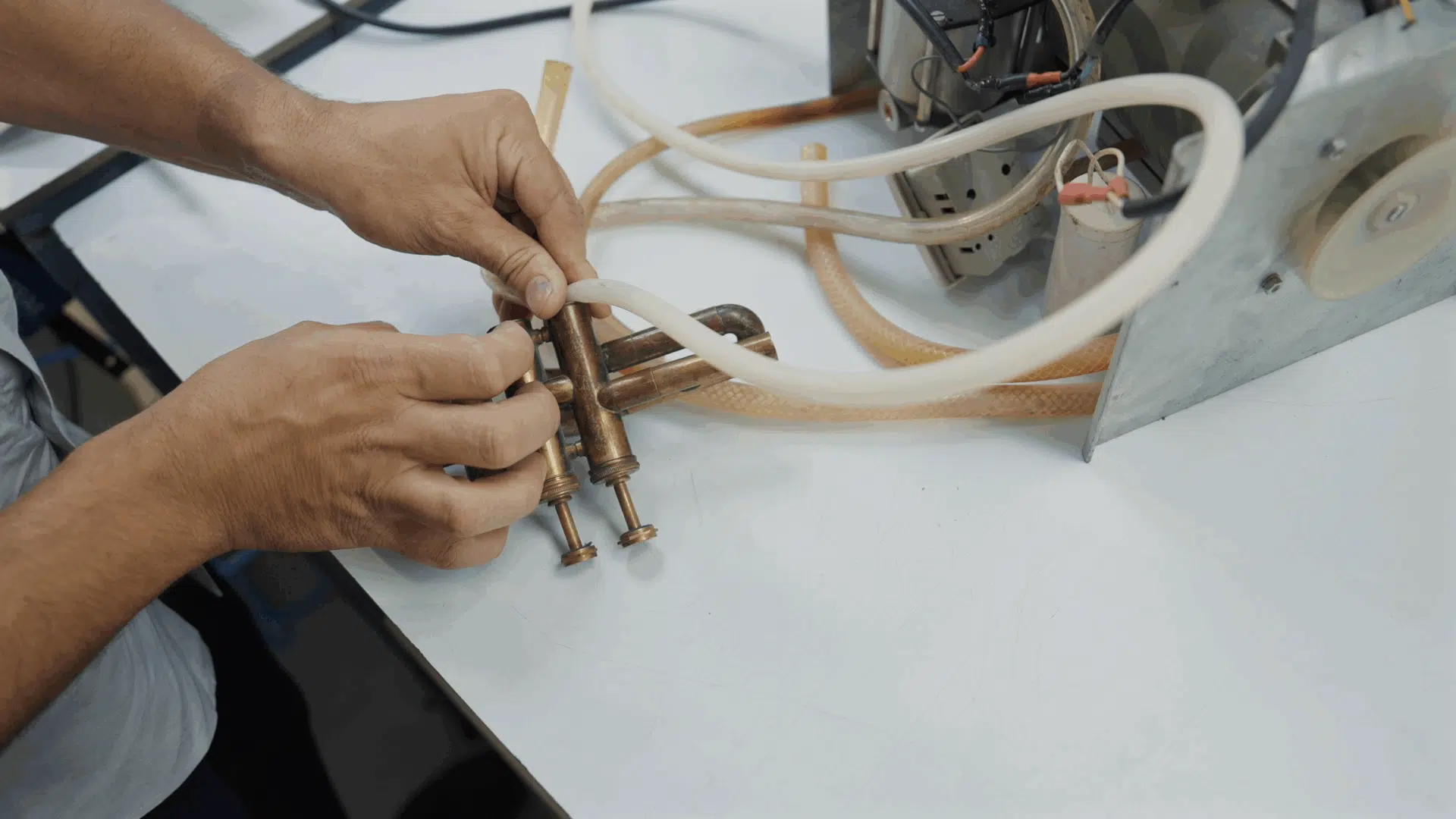

On the floor nearby rests a massive silver-painted tree trunk, its hollow interior ready to host a breathing apparatus—one not based on a digital recording, but on air manipulation engineered like a brass instrument. On the crowded work table, new sculptures are in different stages of becoming: a clay seed shaped unexpectedly like a brain, two mannequin arms, wax and metal frogs, rats, pigeons and crows—a cast of characters gathered in anticipation.

Along the back wall, an immaculate tool board stretches across the room, lined with wrenches, spanners, drills and drill bits. Beside it stands a cupboard that looks like it once housed a library’s card catalogue—except here, instead of index cards, each drawer holds neatly organised wires, tiny motors, gears and metal fragments. His wife, the artist Rithika Sharma, jokes that this is the tidiest the space has ever been.

As we speak, Shailesh plugs in a new contraption—two delicate brass spoons connected to a hydraulic motor programmed to thrust forward at timed intervals. The machine breathes loudly, letting out an elongated “pst,” like a bus releasing compressed air. “My machines,” he says, “perform the way we perform rituals.” Watching the spoons tremble gently, their movement exaggerated and self-conscious, the analogy is hard to miss.

Growing up in a small village in South India without electricity, Shailesh first encountered machines only during his higher studies—an introduction that produced both awe and amusement. Before art, he studied Sanskrit, and the analytical framework of Tarka Shastra still shapes how he approaches an object: examining its beauty, function, inner meaning and extended metaphorical life.

“My practice is a reaction not just to an object,” he explains, “but to its sensibility — its political, cultural and social weight.”

His ideation begins in drawing. The notebooks and sheets of typewriting paper scattered across his studio are filled with text, rough sketches and notations that reimagine mechanisms, map out systems and conceptualise possibilities. Art, he says, has always been a way to register ideas in a given moment, to test one’s own assumptions and expose systemic contradictions. “I simplify complex machines so they can reflect human needs and wants—like the unnecessary mechanisms society creates all the time.”

Across the room, his collages add another layer to this inquiry—drawing from palmist storefront signage in his village, bureaucratic lettering from government forms, fragments of maps, instructions, dioramas. Text winds through these works like marginalia from a private manual of the world. “I never studied in an English-medium school. On a typewriter, I can write without knowing anything,” he says. “My writing is more free-flowing, without being too conscious about grammar or syntax.”

He has been an artist in residence at world renowned institutions, including most recently the International Centre for Theoretical Sciences (ICTS) in Bengaluru and CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Geneva – with the world’s largest particle physics laboratory, where scientific inquiry and philosophical speculation converged in unexpected ways. His work has travelled widely—from Villa Arson in Nice to Savvy Contemporary in Berlin, from Daejeon Museum of Art in Korea to Colomboscope in Sri Lanka.

Yet here, in this small basement in Noida—surrounded by machines waiting to breathe, motors awaiting tuning, and typewriters waiting to unleash a word salad that may or may not inspire his next work—one thing is clear: his practice is less about the objects and more about the systems they expose—ritual, belief, logic, and the strange negotiations between these systems. Everything here, whether the brass spoons welded together, the two mannequin arms or the typewriter, is an invitation to examine the mechanisms that rule our many worlds.

“Machines in and of themselves have no logic,” he tells us. “And yet we help each other find wonder in the world.”

Born in 1986 in Karnataka, Shailesh BR lives and works between Greater Noida and New Delhi.