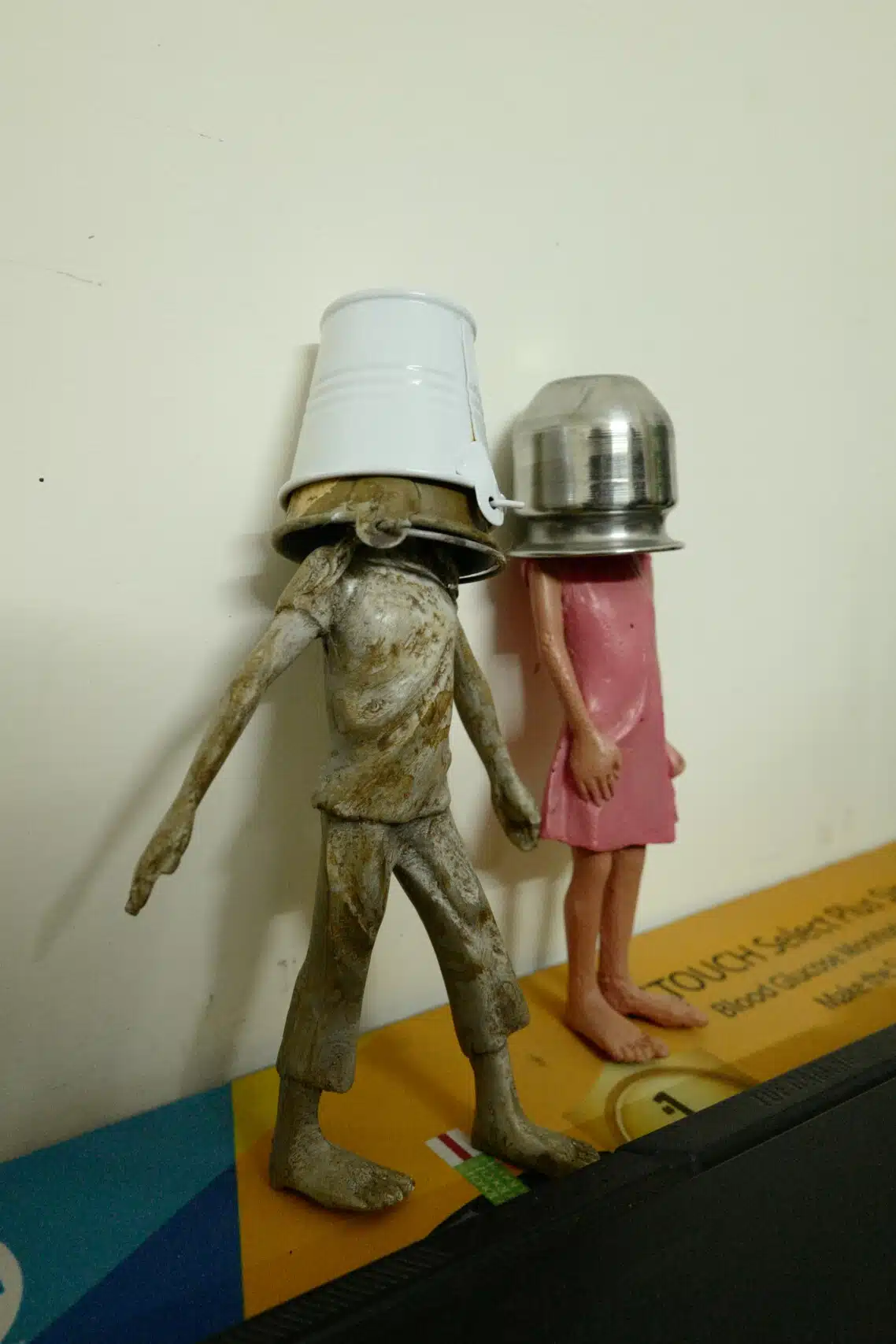

When you look at Mohd. Intiyaz’s Chotu, a sculpture of a boy with a bucket on his head, there’s an irresistible urge to lift the bucket and peer underneath — to see the face of a child who might remind you of the young errand boys ferrying chai through the lanes of Mumbai or Delhi. The figure is specific, yet strangely ubiquitous. It stirs up something familiar, a twinge of nostalgia, perhaps, for the simplicity and struggles of childhood that we may not have personally experienced, but have encountered at some point in our lives.

Children often appear in Intiyaz’s work. His studio, located in a small four-by-six-foot room in his house, which he shares with his wife, Shabnam (Saba for short), is surrounded by families with children, and a school named ‘Super Genius’. These children are often forced to grow up and take on adult responsibilities early in life due to socio-economic circumstances, with many leaving behind their dreams and schooling for a daily wage. Drawing from his own memories of growing up as a migrant from Jharkhandi, whose family moved to Delhi in the hope of a better life, Intiyaz turns his stories of displacement, alienation, art in studio to reflect on memories, as well as the lives of these children, many of whom come from marginalised or migrant families without a secure familial support system to rely on. His goal is to ensure that these stories are neither overlooked nor forgotten.

After completing his MFA from Jamia Millia Islamia, Intiyaz slowly came to understand that what started as personal recollection soon became a way for him to grasp how widespread these experiences were. He realised that these stories were not isolated; they echoed through lanes and across cities. This realisation sparked a deeper inquiry: why do social structures consistently fail the most vulnerable? Why are such realities still difficult to confront or even talk about? Rather than offering easy answers, Intiyaz channels these questions into his practice by championing the resilience of the children around him. Through his work, he gives their lives a sense of dignity and weaves them into his art to share their stories with the world.

We spoke to Intiyaz in his workspace as the artist took us through his studio tucked away in the middle of a market in a 200-square-foot space, sharing stories of his journey, childhood, and the children in his community who inspired the works on his walls.

WHERE DO YOU WORK?

Originally, my studio used to be in Tahirpur, which is just about 100–200 metres from here. It was a small 10 ft x 5 ft room where I worked, though it was difficult to create large artworks there. The good thing was that it was in the middle of a busy area, and it felt like life was unfolding outside, and I was able to capture it on my canvas and in my drawings. At some point, I thought that if I could find a home nearby, I would just live there and stay connected to the area and its stories.

That’s how I ended up taking this new place with a bedroom and a studio. I use the whole house for my work. If I have a big project, I have enough wall space; for smaller ones, there’s the table and benches. But for the stories, I have to go back — to stay connected with the changes happening there. Many times, while observing the situation, I found that nothing has really changed.

YOUR WORK IS DEEPLY CONNECTED TO YOUR NEIGHBOURHOOD. TELL US MORE ABOUT THIS RELATIONSHIP AND ITS INFLUENCE?

I started taking tuitions to get to know the children in the neighbourhood. I would talk to them, and they would share details about their daily lives — their school day, incidents they experienced, the struggles of fetching water, their home environment, and their relationships with their parents.

I’m also part of some local groups, like the RWA (Resident Welfare Association) and other organisations. Important issues often came up in our conversations — like a missing child. I always feel connected to the people and their concerns. Even now, whenever I get the chance, I go and spend time with them and listen to their struggles.

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE STUDIO? HOW DO YOU ORGANISE IT, ESPECIALLY YOUR TOOLS? IS THERE A PARTICULAR ORDER?

When I first moved into this studio, I faced some problems. My earlier studio was small, but I was used to it. I knew where everything was and never had to search for anything. When I moved here, it took me a few months to settle in. I started eating and sleeping here just to get used to the space more quickly. Gradually, I began organising everything.

Now, when I walk in, even if I don’t have any work, my mind automatically switches on. If I go to my bedroom, I feel sleepy, but in this space, I’m in work mode. Whether it’s a project, a call, or anything work-related, I’m focused. I don’t know what it is, but when I’m here, I feel creative. The moment I step out, my mind drifts in another direction.

IT’S INTERESTING HOW STUDIOS INFLUENCE THE WAY WE THINK. MOST ROOMS SERVE A FUNCTION, BUT THE STUDIO FEELS DIFFERENT, FREE FROM THAT BURDEN. EVEN WHEN WE IMAGINE OR REFLECT, IT’S THIS SPACE WE TURN TO. WHAT IS IT ABOUT YOUR STUDIO THAT MAKES IT A SPACE FOR INSPIRATION, NOT JUST FOR YOU, BUT FOR OTHERS WHO VISIT?

I would often lock myself in here. My wife used to get worried, and she’d call my parents and say something strange was going on. “Why is he locking himself in a room?” she’d ask. Then my mother would call, asking what was wrong. I’d explain and tell them to give me some time. When my wife comes in now, she says the space makes her sleepy (laughs). In the beginning, I had to adjust to this environment too, but now I’m very clear — this is the place where I think and get ideas. It’s a powerful space. The moment I sit in this chair, my mind starts working. If I sit anywhere else, I can’t focus.

WHAT ARE YOU WORKING ON CURRENTLY?

This year, my projects have been focused on children. Since 2024, I’ve been working on Chotu — a theme I drew from my own childhood. When I migrated to Delhi as a child, my parents told me that if I wanted an education or a career, I’d have to stand on my own feet and support myself. So, I started working at a very young age, selling balloons and earning enough to pay for my tuition. As I got older, I worked as a waiter and did other odd jobs. At the time, I thought earning money to support yourself and your family was just a normal part of growing up.

It was only later that I realised how much I had missed out on, such as spending time with friends. Now, when I see children working, I see myself in them. There are two kids who come to collect garbage from my house — one is seven, and the other is ten. They go to school, but I can see that, like me, they’re losing their childhood. That’s what led me to start the Chotu series. It’s something I’ve had to read and research a lot for. There are Chotus all around us — in the market, in the streets. What I’m trying to do now is reflect on these realities and think about how to make my art more impactful.

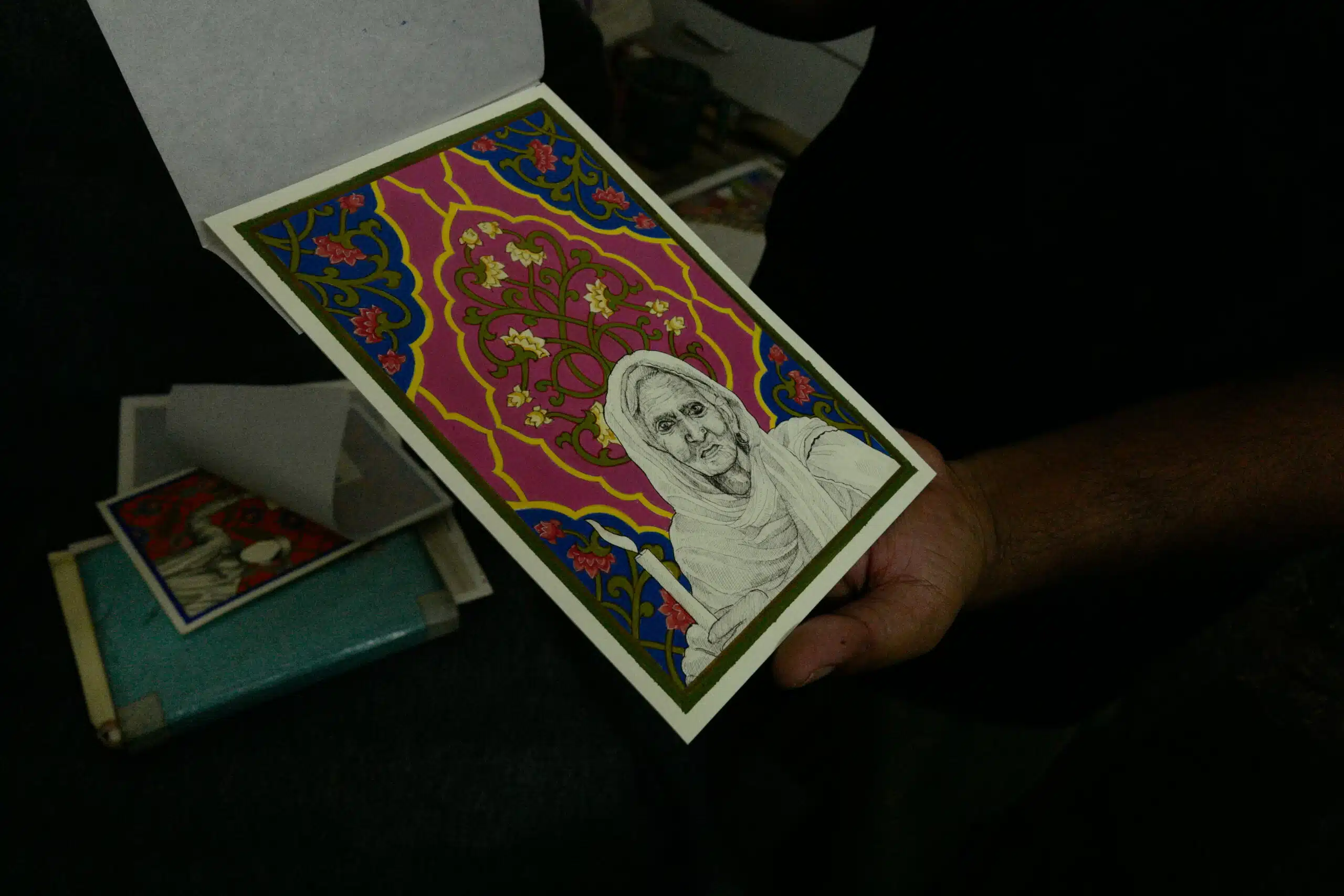

I’ve started working on realistic portraits. I take a lot of live photographs of children of various ages, either from my own family or from the neighbourhood, and then I make sketches based on the photographs, which I then develop into paintings.

Mohd Intiyaz (b. June 6, 1996, Jharkhand) earned his BFA and MFA in painting from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, and lives and works in Delhi.