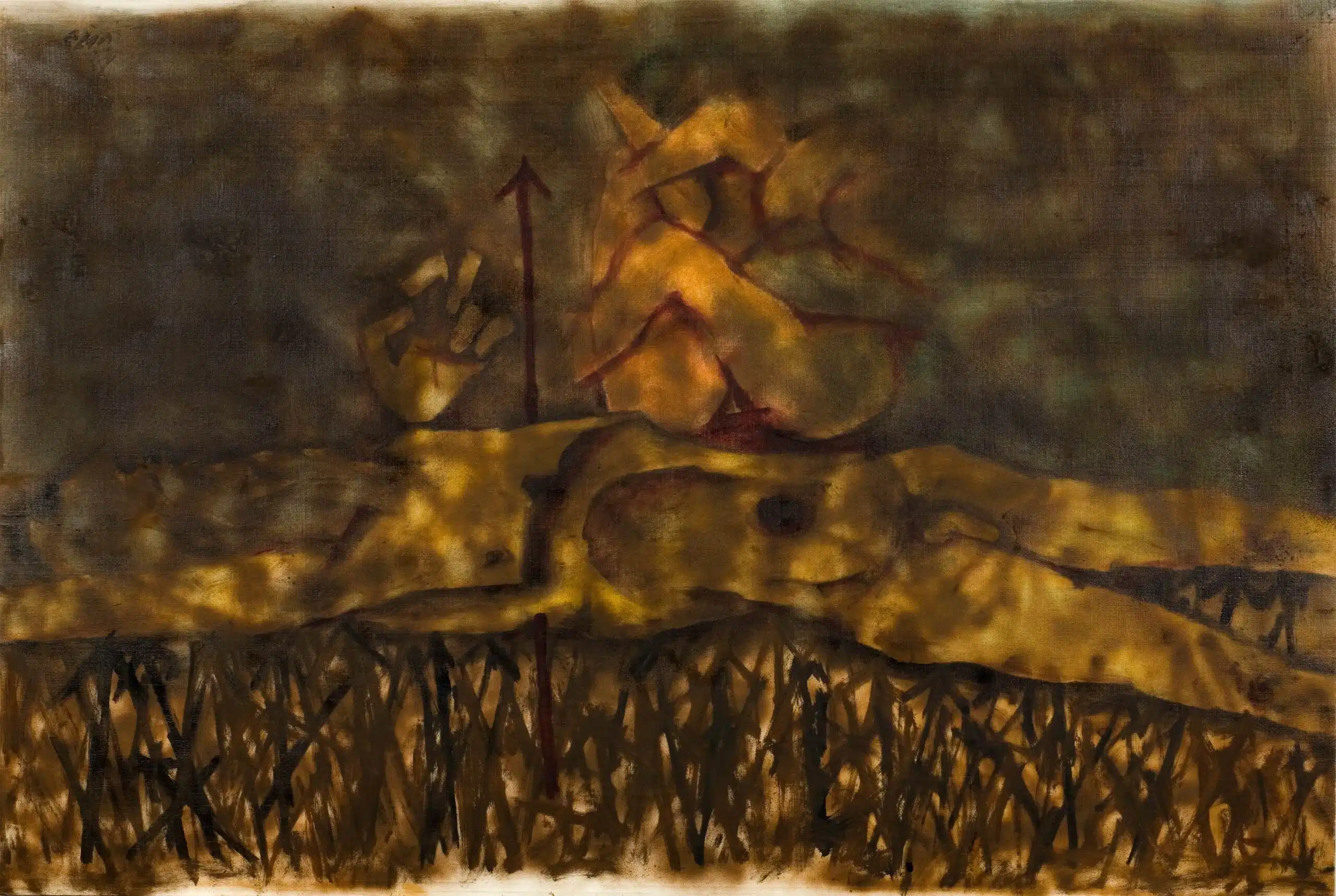

Sunlight strikes the recumbent body of Bhishma, grandsire of the Kuru clan, through clouds of dust and smoke. He lies on a bed of countless arrows that have pierced his flesh, suspended on the battlefield between earth and sky, life and death. A single arrow rises emphatically skyward at the level of his heart, his hand partially opened in an indeterminate gesture. Bhishma glows like a holy body burning on a smouldering pyre of smoke, dust, and ash, while strange figures gather above his naked, vulnerable form.

The conditions that brought this virtuous hero to this critical moment are far too many and complex to elaborate in detail — a culmination of karmic forces and crossed destinies that find retribution and resolution in his demise. Bhishma, who has the ability to choose when he dies, hovers in liminal suspension for 58 days, waiting for the auspicious period that follows the winter solstice, when sunlight will overpower darkness and the night-time of the gods will transition to day. His death is one of the darkest hours in the Mahabharata – a major Sanksrit epic of ancient India – and like the cosmic forces that compel spring to follow winter, it signals the approaching triumph of light.

“Bhishma’s death is one of the darkest hours in the Mahabharata – a major Sanksrit epic of ancient India – and like the cosmic forces that compel spring to follow winter, it signals the approaching triumph of light.”

The image of Bhishma on his bed of arrows appears in at least six works by M.F. Husain in the Herwitz Collection at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. His Mahabharata series of prints, produced in 1983, opens with a similar composition, featuring a quote that lucidly conveys the artist’s interest in representing the epic battle: “…The Mahabharata discloses a rich civilisation and highly evolved society which, though of an older world, strangely resembles the India of our time…”

M. F. Husain. Bhishma, 1971. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum

Husain’s persistent engagement with the fate and future of India is visualised through an extraordinary range of references, from the historical past to the popular present of his lifetime. His genius resides in his masterful application of symbolic forms and gestures, pulled from the rich wellspring of Indian iconographies and tales of yore. Using this language, Husain speaks to us of our own times and struggles.

This particular painting was part of a series of 29 pieces on the Mahabharata produced for the 11th Bienal de São Paolo in 1971, at which both Husain and Pablo Picasso were offered an exclusive exhibition space. Picasso’s Guernica — a spectacular vision of the traumas and tragedies of war — inspired Husain to take up scenes from the ancient Indian epic. He stated, “…only Picasso could do it justice, [but] he’d not done it. Let me try.” Authentically Indian in scope and history, and truly universal in its moral lessons, the clash of the Kauravas and Pandavas made for an ideal subject to explore at the biennale.

“Husain’s persistent engagement with the fate and future of India is visualised through an extraordinary range of references, from the historical past to the popular present of his lifetime.”

For those familiar with the Mahabharata, the aged, defenceless figure atop a profusion of arrows would be instantly recognisable as Bhishma. The scene’s context and its many narrative threads all come to mind through only the barest, most essential iconography. Husain has no interest in reproducing a detailed visual account of this mythic moment — there are no Pandavas or Kauravas in attendance, no celestial beings or heavenly swans in observance, no blessed spring from his mother, Ganga, to quench his thirst. As such, even a viewer unfamiliar with the story finds countless associations. Vulnerable but magnificent, Husain’s Bhishma is Christ-like in form and reminiscent of the sacrificed Saint Sebastian, who also endured a volley of arrows before his eventual death.

Husain’s painting requires viewing through the widest possible lens to touch upon its many possible interpretations. To situate his work within one specific tradition or to restrict its meaning and value to a single country is to deny the universality of his particular artistic genius. Ripe with potential readings and rich with contemporary concerns, his works are as relevant today as ever before.

Born in 1915, M.F. Husain was one of India’s most significant modern painters. He is renowned for his distinct visual language that combines traditional iconography with secular themes, and was a founding member of the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group in 1947.