“The studio is a fluid concept that I carry within me,” artist Lakshmi Madhavan tells us. Born in Kerala, based in Mumbai, and having moved homes throughout her adult life, Lakshmi is an artist whose materials and mediums shift along with her surroundings. From drawing to textile to large-scale installations, the artist is constantly expressing the questions most on her mind: what is a body, what is a woman’s body, and how does it express, celebrate or rebel against social and cultural conventions.

“I start my work in the studio at 8am in the morning after dropping my 3-year-old son to school,” she tells us, taking us through a typical day as a mother and artist. “Some days, I don’t have that luxury, and I carry my work and my thoughts with me, and work on them after putting my son to bed at night.” Work for the artist means different things on different days. Some days, it means absorbing the scenes of the city and writing down her thoughts on her phone and other days, it could be working on bringing a textile design to life with weavers of Balaramapuram — a weaving district in her home state of Kerala which she frequents from time to time.

“The artist came to kasavu as a way of honouring her grandmother, whom the artist remembers as always wearing pristine versions of the mundu veshti, the traditional Malayali attire.”

For Lakshmi, becoming a mother in 2018 was one of the most transformative experiences in not just her personal life, but also in her career as an artist, giving her “a new way of looking at the world and a new interest in questioning everything.” The roles of ‘mother’ and ‘artist’ are not separate to her but blend into one another as a creative, vulnerable and tender process. In fact, she lays out her artistic process parallel to a bedtime conversation with her son, who she believes is “a greater artist than me”. In one example, she tells us about his inspiring response to a reading of The Very Hungry Caterpillar: “But why does the caterpillar want to become a butterfly at all?’. “It is this kind of relentless curiosity that art requires and it is what motivates me these days,” she says. “You flip an idea around, deflate it, inflate it — there is always something alive.”

Lakshmi began her career not as an artist, but with a corporate role in marketing and communication. She only returned to art, a childhood passion, after moving to Copenhagen, Denmark in 2015, that emerged as a mode of expressing her sense of alienation that she felt in this new country. “Art saved me in so many ways,” the artist attests. “I didn’t even know I had any art left in me. It had been many decades since I had picked up a brush or a pencil.” Yet, motivated by urgent questions about the place of her brown body in the world and inspired by other feminist artists like Mona Hatoum and Louise Bourgeois, the artist’s initial “doodles” became fully realised into anatomically-inspired works on paper and found object collages, processes through which she found a language of questioning identity and gender politics. In her early career, she was also mentored by artists like Jitish Kallat and Bernhard Martin, who helped her come into being as a practising artist.

Download artist posters here >

Download artist posters here >

Of late, the artist is spending much of her time in Balaramapuram, a central hub of kasavu weaving in Kerala, the primary material of the artist’s works in recent years. The kasavu mundu veshti, the traditional Malayali attire, comes with highly coded designs and ways of wearing, depending on its wearer’s gender, class and caste. The artist came to kasavu in a second turning point in her career, as a way of honouring her ammamma or grandmother, whom the artist remembers as always wearing pristine versions of the mundu veshti. “Ever since growing a body within me, the nostalgic smell of my ammamma’s veshti became ever-present for me, and I started to become increasingly aware of the fact that my ammamma, in small and surprising ways, had been my first feminist role model,” the artist says. “I needed to find a way to translate this story for my son.” The kasavu became like an umbilical cord for the artist that helped her travel back home to her roots and act as a metaphor for the memory and passing-on of her lineage.

“I am always striving to work from a place of absolute honesty, and that means questioning what I am doing at every stage.”

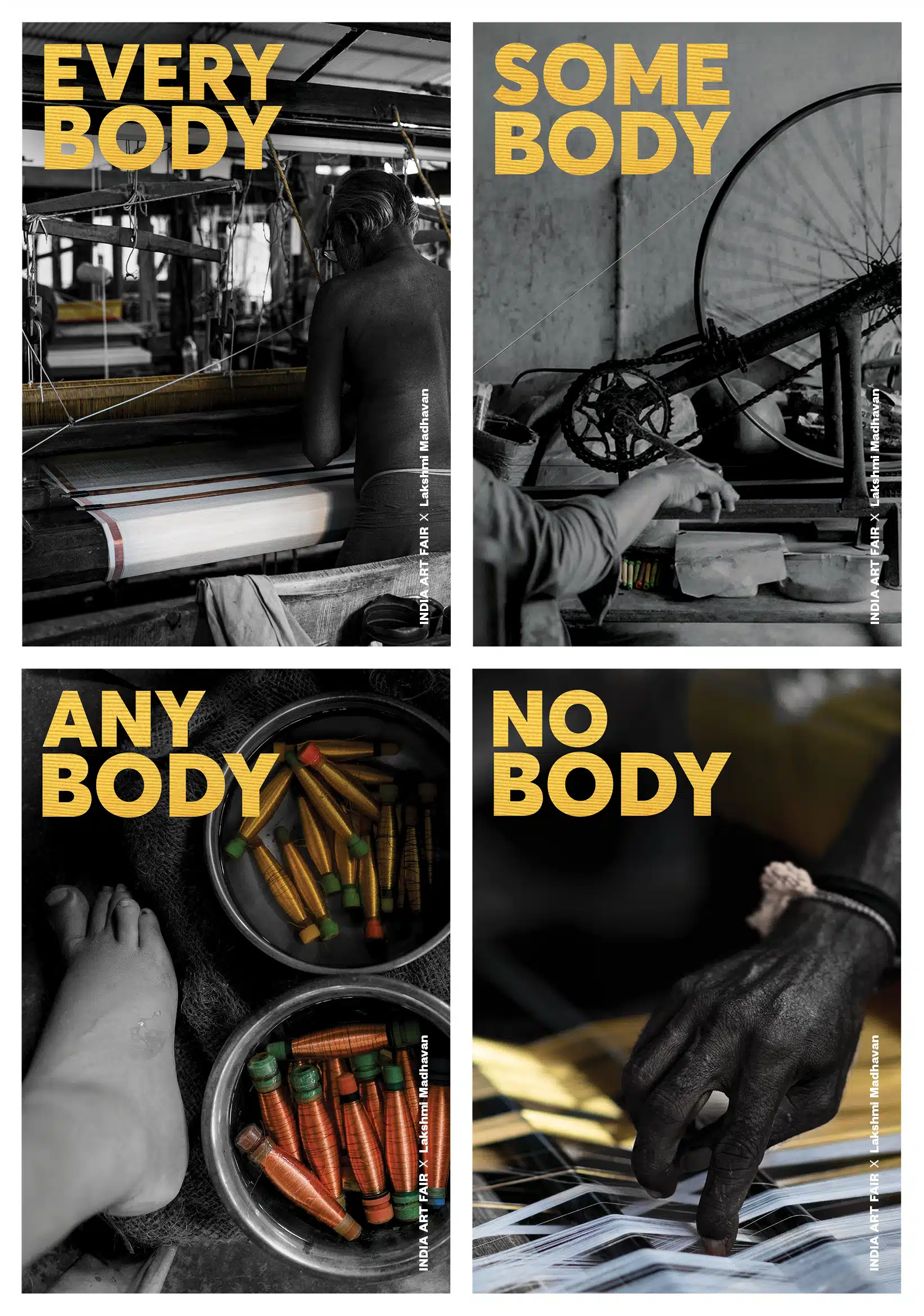

“I am always striving to work from a place of absolute honesty,” says the artist. “And that means questioning what I am doing at every stage.” While the personal memory of her grandmother formed the emotional core of her interest in the kasavu mundu veshti, Lakshmi’s questions grew into larger social ones about whom the kasavu belongs to and who is able to tell its story. In a 2022 work from the series, Hanging by a Thread, that was displayed at the National Museum in New Delhi, the words ‘some/body’, ‘every/body’, ‘any/body’ and ‘no/body’ were woven into the border of a kasavu veshti, referencing the weavers’ bodies that laboriously weave the kasavu, and yet, are the very same bodies that are eventually not allowed to wear it. “I want to craft a kasavu that is universal, one that goes beyond being a marker of the body,” shares Lakshmi in a statement that summarises her practice.

The kasavu weaving community in Balaramapuram is dwindling, placing the future of the craft at a precarious position. Lakshmi, however, aims to reimagine the future narrative of this art form. She is working on community-led interventions that includes innovations such as the nano loom — a more compact and cost effective model as compared to the bulky wooden loom used traditionally. In all of this, the artist is clear that her motivation is not to “change the world”, but only a question: “what stories will I and my art leave behind for the next generation?”

Lakshmi Madhavan was born in Kerala in 1986 and works as a conceptual artist, based primarily out of Mumbai. Her artist poster celebrates the weavers of Balaramapuram, the invisible bodies that weave the gold and white magic of the kasavu.