Aharoni moves fluidly across sculpture, installation, furniture and language, yet remains anchored in a single pursuit: understanding how meaning travels through time, ritual and collective memory. Drawing from lived experience as much as from philosophy, he treats time not as a backdrop but as a material—non-linear, porous and alive—where past, present and presence coexist. Objects in his studio are vessels carrying memory, energy and narrative, often rooted in domestic life, sacred symbols and inherited traditions that cross borders and belief systems. Language, for Aharoni, is equally sculptural. His constructed scripts—most notably Hebrabic© and Hindru©—collapse binaries between cultures often framed as oppositional, questioning the very idea of linguistic or cultural purity. Letters become energetic forms, vibrating beyond legibility, inviting visceral rather than purely intellectual engagement.

Across his work, authorship dissolves into shared humanity. What emerges is a practice that resists resolution, remaining open, relational and deeply human. Before his presentation at India Art Fair 2026, we spoke with him to understand his inspiration and his process.

Your work often unsettles inherited ways of seeing. Your practice draws from many disciplines and cultural sources. How do you think about authorship when working across inherited traditions, collective memory and contemporary making?

Authorship is a fascinating and complex concept. When we think of rituals, traditions and cultural narratives, how do we ultimately know the source or author? When individuals—or entire communities—migrate, rituals, narratives and traditions are shared, modified, adapted or adopted by others. Who, then, is the author?

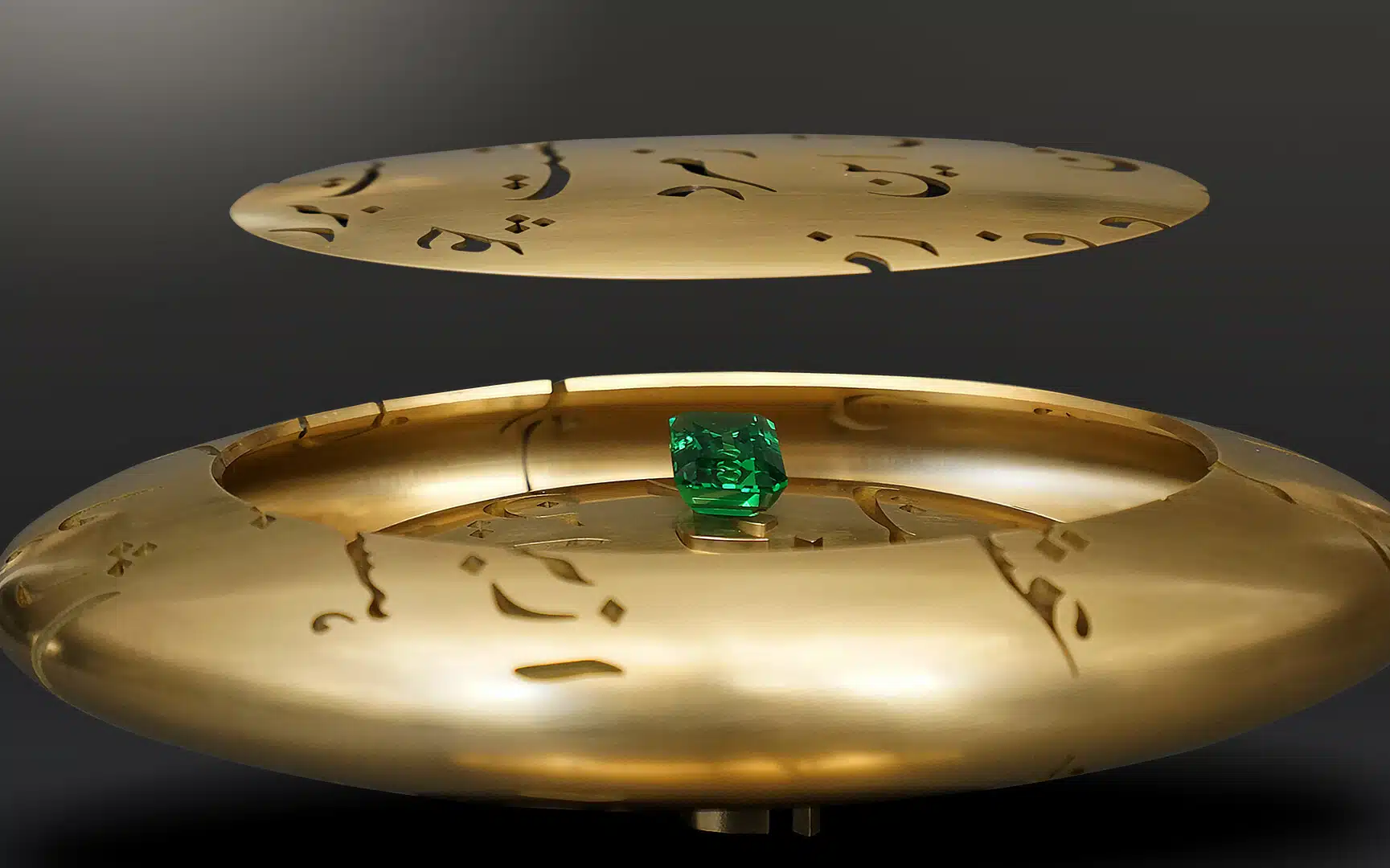

One of the sculptures in the studio, The Immanent Transcendental (The Golden Calf), explores this idea through an icon—the cow or calf—that resonates across cultures, belief systems and eras. It connects narratives ranging from the Judeo-Christian biblical story of the Golden Calf to Nandi, the divine mount of Shiva, among others. Ultimately, the work asks us to see a collective narrative—one that illuminates our shared humanity.

You’ve often spoken of time as a medium rather than a backdrop. How does time shape the way a work begins—before form, language, or material enters the conversation?

The concept of time is a black hole—it is my greatest challenge. I grapple constantly with the idea of non-linear time and its malleability. I feel as though I can sculpt with time. When you say “a work begins,” the question itself assumes linearity. But what if a work existed before it was created? Or what if a utilitarian object was conceived by its maker to eventually become a work of art? Through my practice, I am exploring how we might expand our understanding of time—that there is no past or future, only the present.

Take P’tiliyah. It was my grandmother’s kerosene stove. As a child, I was captivated by it—not only because it was the heart of our home, with cooking happening almost constantly, but because it felt like an art object. The smells, the glow of the flame, the warmth—it carried immense energy. When my grandparents passed away, I asked my family for the stove, which by then was considered obsolete. Years later, in Germany, I transformed that same stove into a working object made of crystal. Growing up, three generations of Yemeni Jews lived under one roof. I remember waking at night and being guided by the light from my grandmother’s stove. That light still exists for me. I lost my parents early, but I don’t experience that loss as absence. I remain connected to them—through dialogue, disagreement, memory, presence. All these energies, across time, meet here and now.

You have described language as an Atlas or a barometer of a culture. Text appears in your work not simply to be read, but to be encountered physically. What interests you in the moment where meaning gives way to form?

Letters are energetic, animated forms. They vibrate with meaning—individually and collectively—as they assemble into words, phrases, stories. When you remove the spaces between letters, or expand them into sculptural scale, that radiance intensifies. Even if someone cannot read the text, they can still connect viscerally to the energetic relationships between the letters. In that moment, form transcends literal meaning.

Your constructed scripts—such as Hebrabic© and Hindru©—merge cultures often framed as oppositional. Are these languages acts of reconciliation, or provocations that question the idea of cultural purity altogether?

This question brilliantly hones the entire concept of the work into its dual essence and your question, in fact, is also the answer. Growing up, both Hebrew and Arabic were spoken in our home. The shift between them was seamless. Only later did I learn that these languages were perceived as conflicting. I remember a childhood friend being frightened when he heard my grandparents speaking Arabic. I explained that we were Yemeni Jews—these were our languages. Yet culturally, I was taught to feel ashamed of that.

Around 2000, I began experimenting with calligraphy, merging Hebrew and Arabic. The reactions were extraordinary—especially from people who could read only one of the two. The process is a dance. Both scripts move right to left, but they demand compromise. Letters stretch to accommodate one another, and like people, if stretched too far, they break. Hindru© introduced another layer. Hindi moves left to right, Urdu in the opposite direction. At India Art Fair 2026, we will present a new Hindru© work—24-carat gold-plated—centred on gratitude.

Whether sculpture, installation, or furniture, your works seem to operate as vessels for ideas. How do you know when a thought has found its right form?

Each work is an exploration of a thought rather than its resolution. Thoughts are dynamic energies —they shift and evolve. Even after a work leaves the studio, it continues to ruminate, for both me and the viewer. I am not interested in definitive conclusions, but in keeping interpretation open.

At this moment in your practice, what questions feel unresolved—and how might they shape the work you are yet to make?

I constantly think about ways in which the work about the reconciliation of cultures can be expanded, how it can further a dialogue about intercultural connectivity.

India recurs in your exhibitions and research not simply as a place but a philosophical terrain. What does India offer your practice?

My first show in India, Missives, at the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum in Mumbai, centred on my mother’s love letters. I was struck by how deeply people connected to it. That connection came from its intimacy—viewers saw their own stories within hers. When I first visited Kochi, it felt inexplicably like home. Years later, I discovered the history of Jewish traders who lived and traded in the Malabar region, moving back and forth for generations. The cultural exchange—from spices to food to rituals—runs deep. I feel free moving between cultures. That freedom feels like magic.

Finally, literature plays a significant role in your thinking. Are there a few books you would recommend to readers curious about the ideas that inform your practice?

The Gift by Marcel Mauss. Written in 1925, it examines the exchange of objects across cultures, elevating gift-giving into a model of reciprocity and empathy. Written in the shadow of personal grief after World War I, it remains profoundly relevant. Gratitude by Oliver Sacks. A series of essays written near the end of his life, framed entirely through gratitude. It is a quiet, powerful reminder of the energy of appreciation. This book always sits on my desk.

Ghiora Aharoni is a New York–based multidisciplinary artist. A Yale graduate, his work is held in major international museum collections including the Centre Pompidou, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Vatican and leading institutions across Europe, the Middle East, India and the United States.