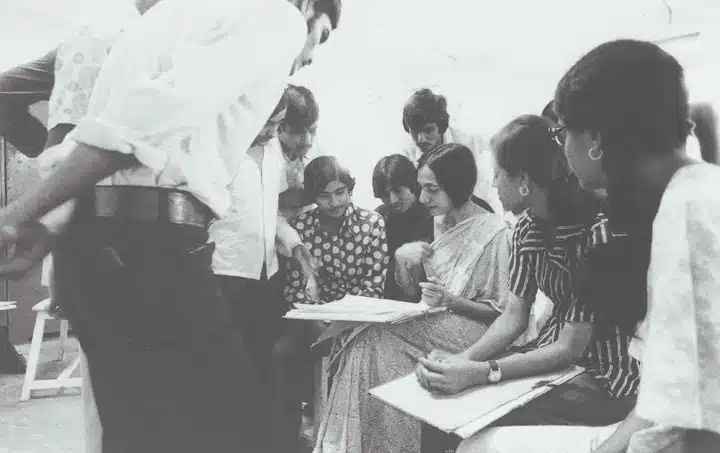

An influential and beloved Indian modernist, Nasreen Mohamedi’s influence on abstraction and minimalism is unparalleled. While her contemporaries M.F. Husain and Tyeb Mehta were making waves in figuration, Mohamedi proposed a sea change with an exploration into abstraction. Her vast travels across countries like Kuwait, Bahrain and Japan, along with her love for Zen and Islamic aesthetics deeply influenced her. She also found inspiration in other, fellow abstractionists, like V.S. Gaitonde.

As she built her practice, Mohamedi’s work grew to be characterised by precise lines, careful composition and a meticulous attention to detail, that gallerist Deepak Talwar once called “poetry within structure”. While she became most known for her experiments with grids and lines, a diary entry from March 1971 tells us that her ambitions were beyond formal perfection. Her intention was also to “grasp [her] heritage with intuition, vision and wisdom – with a total understanding of the present.” Here we explore the world of Nasreen Mohamedi to get a deeper understanding of her work, and abstraction at large.

Nasreen’s marks have a quality of movement.

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, c.1980s. Ink and graphite on paper. 20in x 28in. Courtesy of Akara Art.

Nasreen’s obsessive markings broke out of the grids that sought to bind them. In a diary entry, she marvelled at “little crabs which make those endless patterns”; her marks often echoed the journey of the hermit crab looking for a home amidst shifting sands.

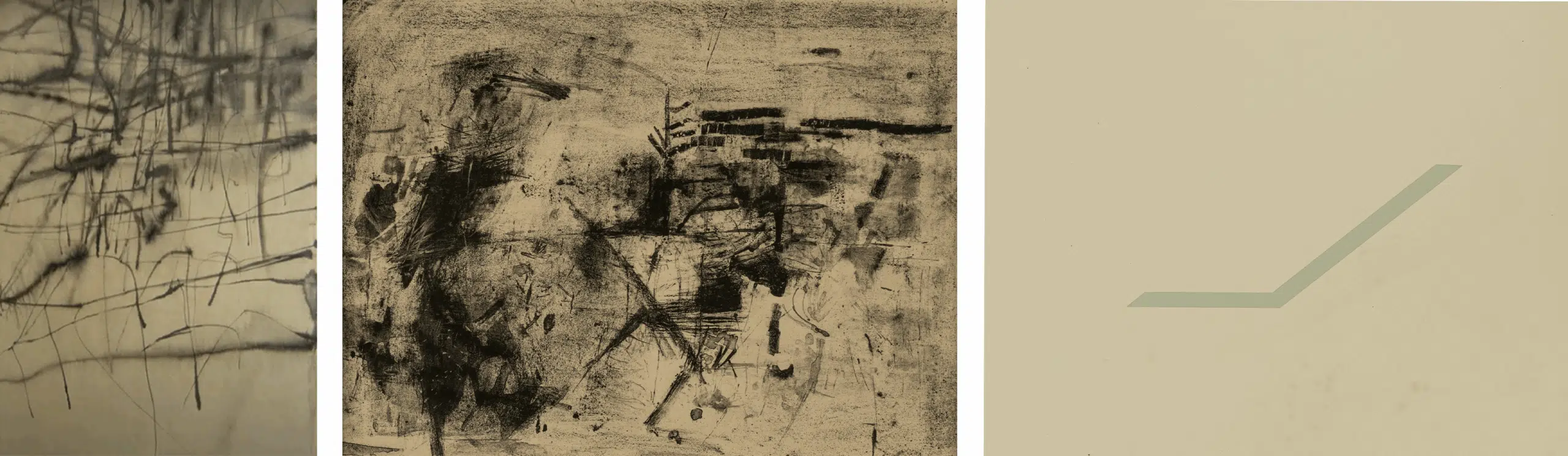

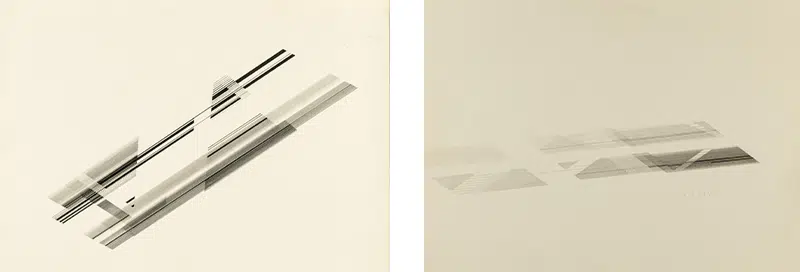

Nasreen’s lines were sometimes spare and sometimes chaotic. Yet, both expressions were part of the same vocabulary.

Nasreen Mohamedi experimented with a variety of lines and mediums including ink on paper, lithography and screenprinting. Images courtesy of Chatterjee & Lal.

Created over many decades, these works show the Nasreen’s evolution as a formalist and minimalist. Her expressive calligraphic paintings sharpened into geometrical, spare drawings. The transformation from somewhat wilder lines into neat, controlled drawings took the artist decades to master.

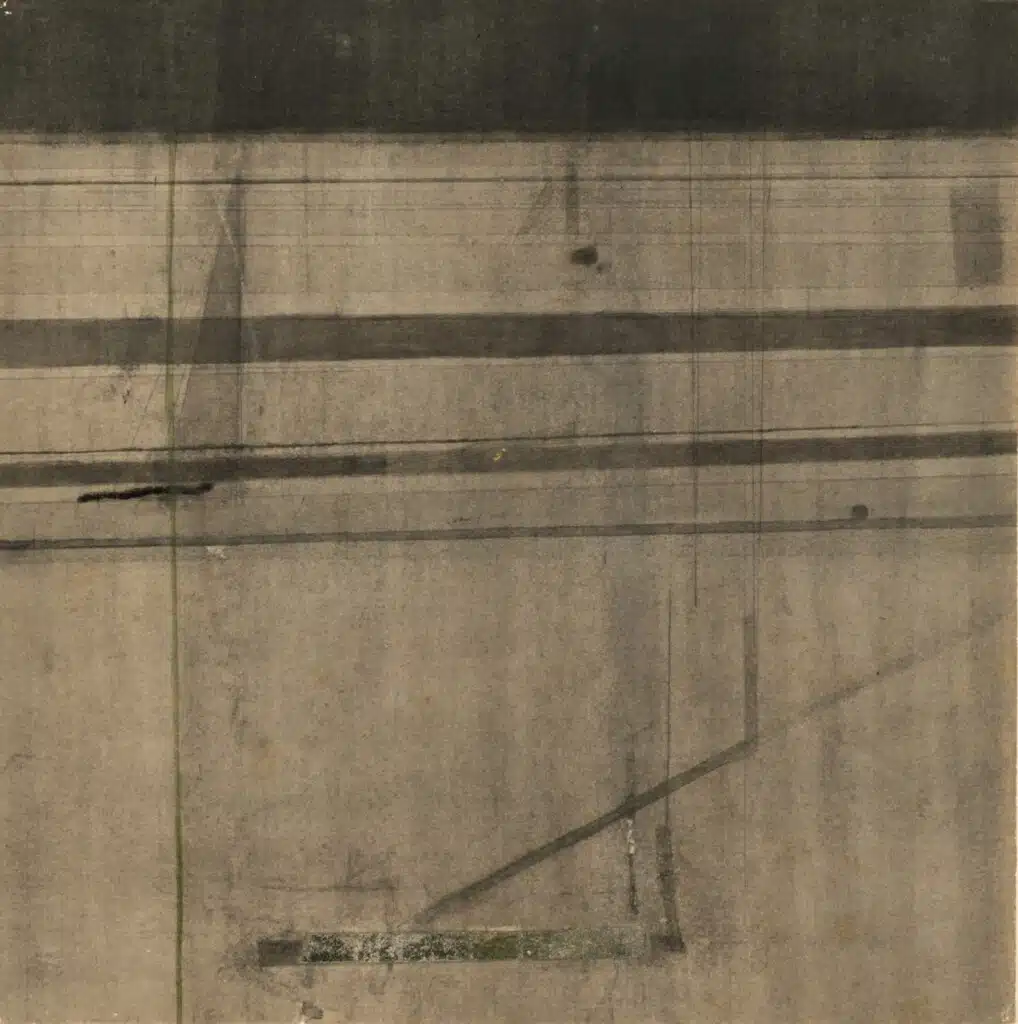

Let’s look at the many smudges in her drawings.

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, 1970. Ink, watercolour and collage on paper. 8.25in x 8.25in. Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery and Glenbarra Art Museum

Nasreen’s early drawings document the process of an artist coming into her own. Her systematic practice of honing and training her skills included erasing and removing “mistakes,” leaving behind only the precise marks she desired. In her diary, she wrote about trying to capture “a thread of discipline” in this “utter chaos”. To do this successfully, showing both the ‘mistakes’ and her carefully honed skills were necessary.

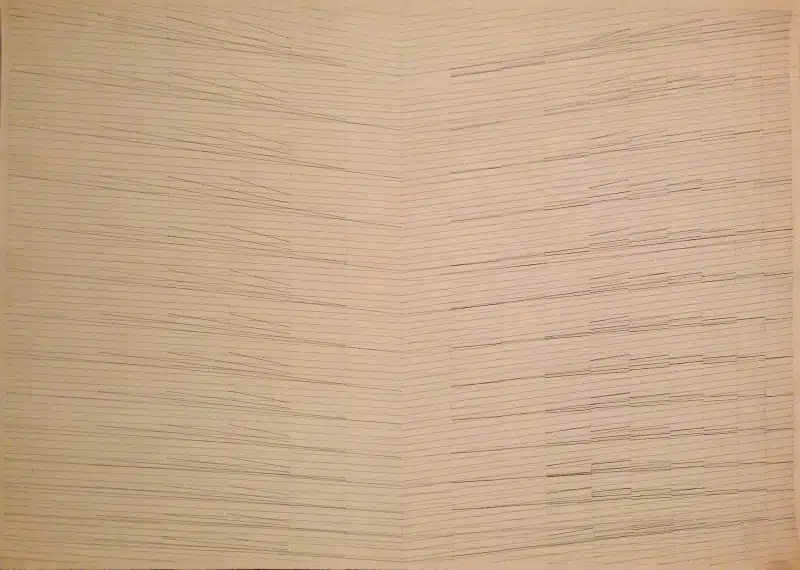

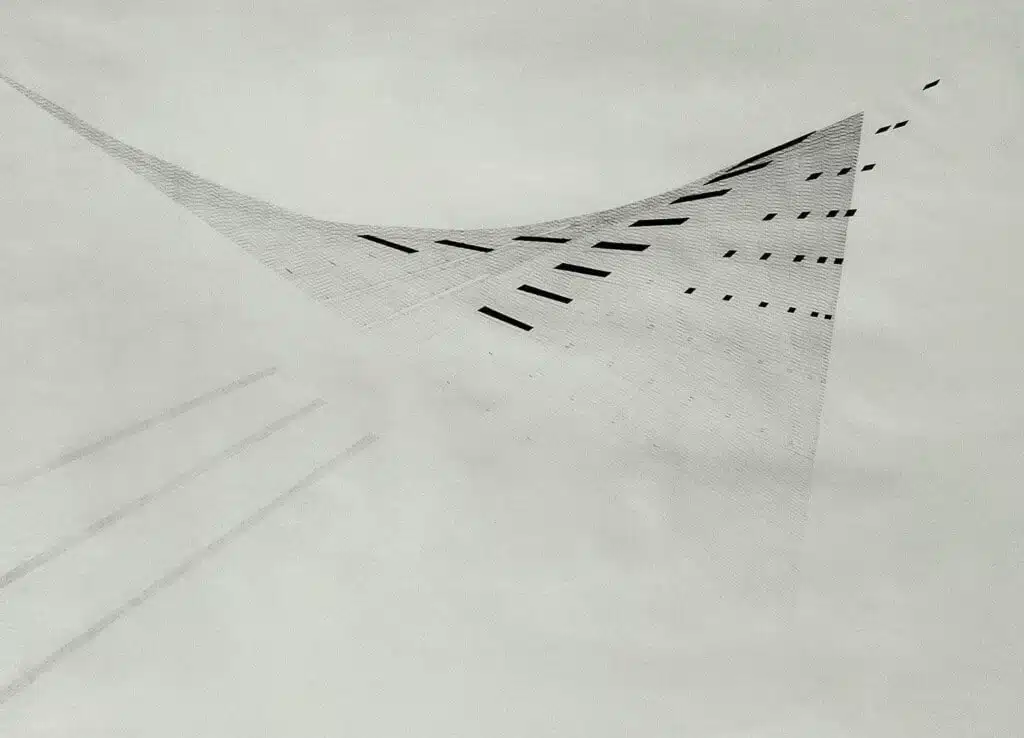

The planes in some drawings seem to float on paper.

Particularly, in the 1980s, Nasreen Mohamedi made several works with ink and graphite with lines arranged in intersecting planes, making the drawings feel three-dimensional. Images courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery and Glenbarra Art Museum.

In Nasreen’s later work, her lines found release from the grid, and took on a quality of electric vitality. Lines and planes lifted off into the air, as if breaking free of gravity’s confines. This is perhaps what gives her drawings a feeling of levity. In one of her many ruminations, Mohamedi likened her work to that of electricians, both involving the “strain between concentration and danger hung on a rope.”

The forms in the drawings reference the artist’s environment, and are open to interpretation at the same time.

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, 1985. Graphite, gouache and ink on paper. 50cm x 50cm. Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery and Glenbarra Art Museum.

In her diaries, Mohamedi noted the connections she saw between the grains of sand on a beach and the expanse of the ocean; her eyes were perpetually drawn to what surrounded her. For her, the miraculous hid amidst the mundane, as she found inspiration in the similarities between mountains and triangles.

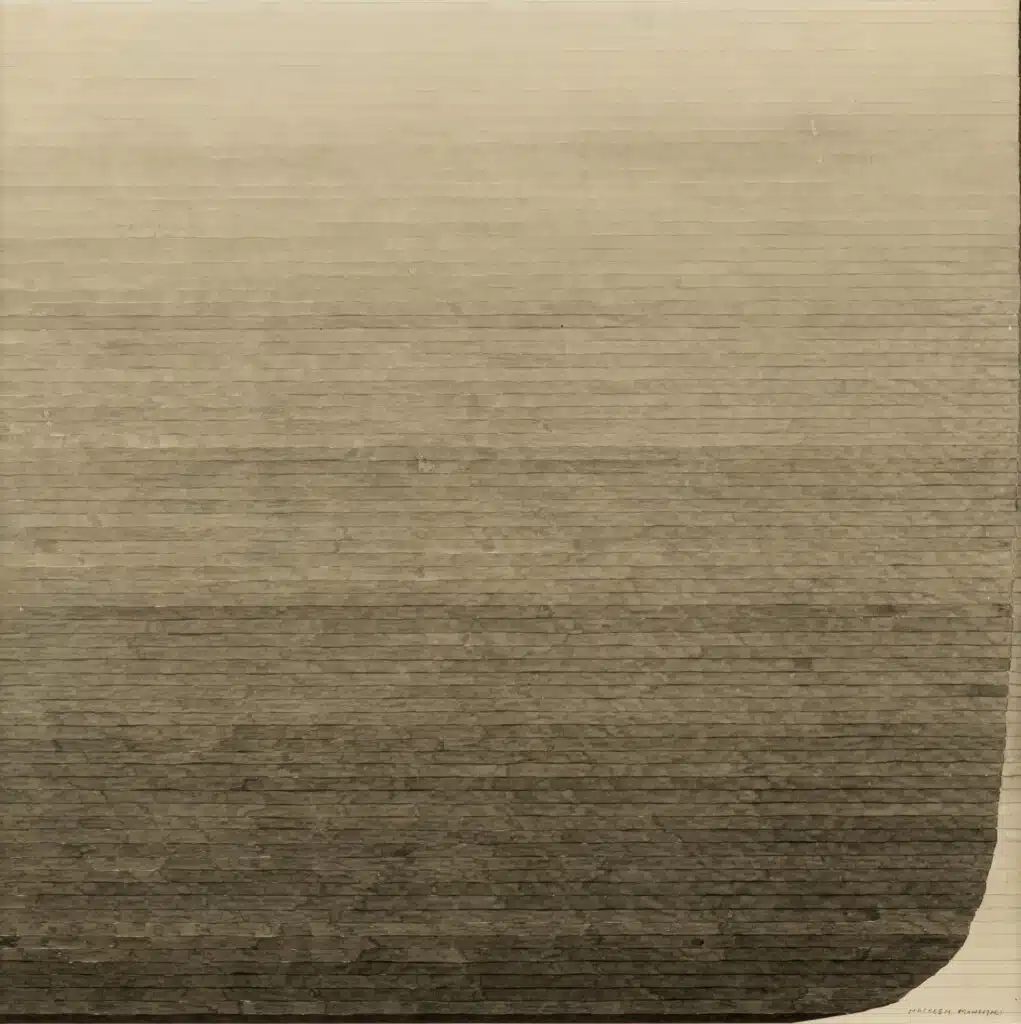

The artist was not afraid of grey space.

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, c.1975. Ink and gouache on paper. Courtesy of Akara Art.

In a talk at The Met Breuer, art historian Sonal Khullar describes the grey zones in Mohamedi’s drawings as “the crux of her art.” Where white space presented a universe of possibility, and black lines marked points of certainty, the grey zones of transition present “the point of departure from form to shadow,” in the artist’s own words.

Now, many decades after Nasreen’s passing, it is clear that her practice will be perennially relevant, and remain an inspiration for anyone exploring the world of abstraction. Her diary entries and artistic gestures will always remind us that there is a pattern to chaos, life in the grey and an animation in what appears to be the most rigid marking — the line.